Over 90 percent of public lands on the Colorado Plateau are open to cattle or sheep grazing. This means that finding places where cattle and sheep haven’t voraciously eaten native plants, eroded, trampled, and compacted the topsoil, or otherwise disturbed the natural landscape is increasingly difficult. How do we know what healthy lands look like without these heavy-footed interlopers?

Important benchmarks for healthy lands

Natural, ungrazed areas without much motorized traffic and that haven’t been heavily logged or overtaken by invasive species are called “reference areas.” When left alone for many years, these areas show us what a healthy natural forest or grassland can look like — as long as invasive plants are kept at bay. That’s where weeding — removing invasive plant species — comes in.

Keeping reference areas free of invasive plants gives scientists, Indigenous communities, land managers, and conservationists a benchmark to show what is possible when lands are protected from truck tires and the hungry mouths and weighty hooves of cows and sheep.

Reference areas are rare

Volunteers run fenceline in an exclosure in Fishlake National Forest in Utah. BLAKE MCCORD

Given the ubiquitousness of grazing, roads, logging, and invasive species, identifying and maintaining these reference areas can be challenging. The Forest Service has a formal designation for reference areas called a “research natural area,” or RNA for short.

The first ever research natural area was established in 1927 in Arizona, and there are now at least 19 sprinkled across the Colorado Plateau, mostly in Utah’s national forests. These research natural areas are generally between a few hundred and a few thousand acres, and include unique attributes like old-growth forests, rare plants and animals, and uncommon alpine or stream habitats found in only a few places on the plateau.

Not all reference areas are research natural areas. Reference areas can also be smaller — like a single creek’s watershed, or even a one-acre area fenced off so that grazing animals — from domestic sheep and cattle to wild elk and deer — can’t reach the grasses and wildflowers inside the fence. Scientists call these fenced-off areas “exclosures.”

Invasive plants are sneaky

Fences, signs, road closures, and sometimes even steep natural terrain are all methods for keeping domestic animals — and destructive humans — out of reference areas. But these barriers don’t stop the seeds of invasive species dispersed on the wind or by animals. What’s to be done? Weeding — or as we like to say, “weeding with a purpose.”

Over the years, dozens of Grand Canyon Trust volunteers have found their purpose, removing thousands of invasive plants that take over because wild animals aren’t eating them. The wonderful thing about persistent and purposeful weeding is that native plant communities, free from the pressures of aggressive invasives and hungry cows or sheep, are fully capable of asserting their presence across the reference area — they just need a little help.

Progress you can see

For the last seven years, Trust volunteers and staff have been putting on their gardening gloves and weeding two unique reference areas.

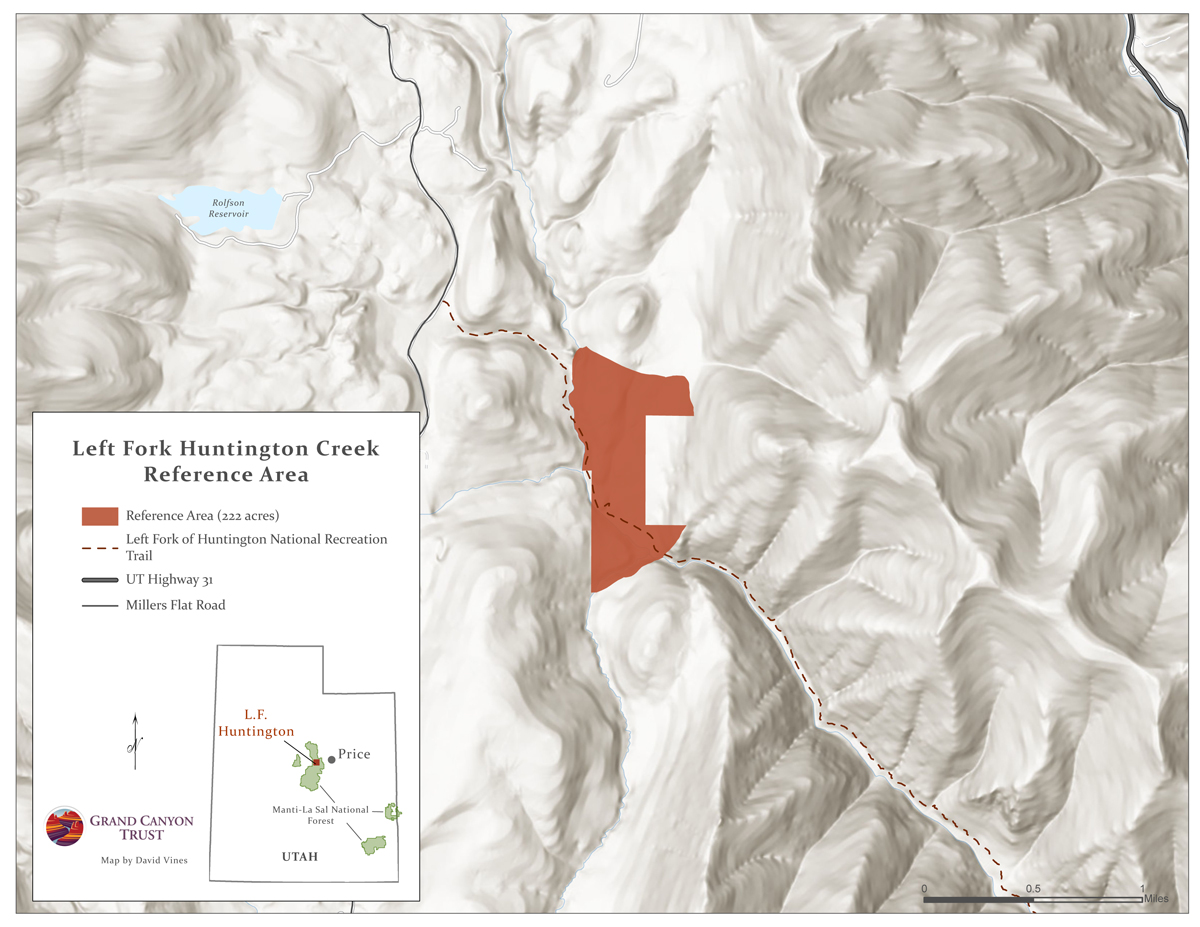

One is the Left Fork of Huntington Creek, a lush 222-acre valley that includes a stream, verdant meadows, and a wide diversity of native plants. Since 2002, the valley has been largely protected from grazing. Free of roads, this reference area offers a rare example of healthy natural conditions for the Manti-La Sal National Forest and provides excellent opportunities to assess the impacts of climate change, another disturbance that cannot be fenced out.

When the Trust’s volunteers weeded the Left Fork of Huntington Creek in 2014, they pulled more than 11,000 individual plants — primarily musk thistle, houndstongue, and salsify. These invasive species evade wild animals who are not adapted to eat them, and invasive plants are generally prolific reproducers, so they can quickly colonize and take over an area, outcompeting the native plants for sunlight, water, and nutrients. In 2021, volunteers removed just over 1,500 invasive plants from inside the reference area, and another 1,800 weeds from areas next door, from which seeds might travel. An 86 percent drop, from 11,000 plants to 1,500, shows just how effective some simple old-fashioned weeding can be.

Weeding the Pando aspen grove

Volunteers have also weeded Utah’s beloved Pando Clone aspen forest since a portion was fenced off to protect it from hooved animals. New aspen shoots were being eaten by cattle and deer while they were still seedlings — and without new growth shooting up, Pando could die.

In 2013, an eight-foot exclosure fence went up to protect a reference area. Trust volunteers have been removing invasive plants from inside this fence, cutting and bagging houndstongue seed heads and flowers. In 2017, volunteers recorded 8,000 houndstongue in their trash bags; in 2018 – just 3,700 plants were found and pulled. In 2019, we cut 5,600 seedheads and plants, but in 2021 we only found and removed 813 invasive plants, a dramatic decline thanks to our weeding efforts year after year. And, the science shows, the aspen are recovering, partially.

How you can help

We want to see the Left Fork of Huntington Creek protected as a reference area forever, and the best way to do that is to designate it an official Forest Service research natural area. The Manti-La Sal National Forest’s management plan is up for review and the public has the chance to weigh in on reference areas, grazing practices, and how best to help the forest adapt to climate change. The Trust, along with our partners, have created a “conservation alternative” for how we think this forest should be managed.