The federal government will determine if the charismatic blue bird should be listed as threatened or endangered.

In promising news for the struggling pinyon jay, on August 17, 2023, the federal government announced that it will review the striking blue bird once common in pinyon and juniper forests across the Southwest to determine if it should be listed as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

Pinyon jay populations nose-dive

Pinyon jay populations have nose-dived, falling by over 85 percent in the last 50 years; another half of the remaining population is expected to vanish by 2035. The bird’s decline is thought to be due in part to the loss of its pinyon and juniper forest habitat. A U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service investigation should help reveal what’s happening to pinyon jays.

Pinyon jays depend on pinyon and juniper forests for survival and those forests are facing a suite of threats. Clearcutting of pinyon and juniper forests, wildfires, and insect infestations have made pinyon nuts harder for the birds to find. Pinyon jays, who forage in large flocks, cache tens of thousands of the nuts in the ground each year. While they remember most of the hidden seeds, the small percentage that they forget become the next generation of pinyon pines. The trees can’t regenerate without the birds and the birds can’t survive without the trees.

Feds to consider protections for pinyon jays

The Fish and Wildlife Service’s decision to consider the pinyon jay for endangered species protections comes more than a year after a petition asked the government to investigate the pinyon jays’ sharp decline. According to the federal government’s August announcement, there is “substantial scientific or commercial information” indicating that listing the pinyon jay as an endangered or threatened species “may be warranted.”

Over the next year, the government will analyze a variety of factors, including destruction of pinyon jay habitat, more frequent wildfires, invasive species, and climate change, as possible reasons for protecting pinyon jays under the Endangered Species Act.

Habitat loss hurts pinyon jays

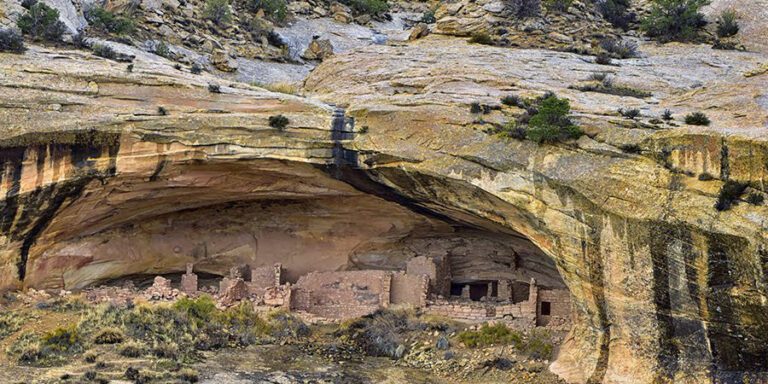

Even though pinyon jays are struggling to survive, federal agencies that manage public lands on the Colorado Plateau are continuing to propose large projects to destroy pinyon and juniper forests. And, to add to that habitat loss, after clearing away forests where old-growth pinyon pines and gnarled juniper trees once stood, agencies often plant non-native grasses for cattle to eat instead. This makes it even harder for pinyon jays to find their favorite pinyon pine seed snacks.

It takes pinyon pines 25-35 years to generate large seed crops and they only really produce masses of seeds after 75 years. Climate change puts added pressure on pinyon and juniper forests. Hotter and drier conditions across the Colorado Plateau make it harder for pinyon pines to produce seeds. And extreme drought over the last 20 years has led to die-offs of pinyon and juniper trees.

What’s good for pinyon jays is good for humans and forests

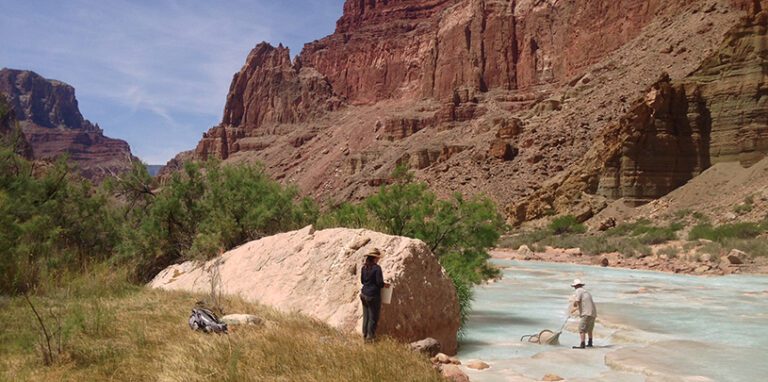

Pinyon jays don’t migrate. They are year-round residents of the Colorado Plateau and they, and many other species, depend on healthy pinyon and juniper forests. Humans too, especially Indigenous communities, rely on thriving pinyon and juniper forests for sustenance.

Listing pinyon jays as endangered or threatened under the Endangered Species Act could help protect more than just pinyon jays. An Endangered Species Act listing might even include designating pinyon and juniper forests as critical habitat, leading to better protections for these forests.

Go birding for conservation

Documenting the locations of remaining pinyon jay populations is an essential part of helping to protect them. The Grand Canyon Trust’s Pinyon Jay Project is one way that you can contribute to this species’ survival. You don’t need any prior birding experience to participate in the project — just keen eyes and ears, your smartphone, and a willingness to listen for pinyon jay calls while you’re traveling across the Colorado Plateau.

There’s a long evolutionary history between the pinyon jays and their forest habitat. The Grand Canyon Trust applauds the Fish and Wildlife Service’s decision to consider pinyon jays for protections under the Endangered Species Act. Meanwhile, we’ll continue advocating for science-based approaches to caring for pinyon and juniper forests, and we’ll continue documenting existing pinyon jay populations.