Native plants have a tough lot — cattle trample them, deer devour them, and invasive species choke them out. Add in climate change and the natural balance of plant communities really gets thrown out of whack.

We work to restore native plant diversity across the Colorado Plateau. Sometimes this means pulling thistles to make space for native plants. Other times it means building fences to keep livestock out, giving delicate grasses the chance to reclaim ground after decades of overgrazing. We count tiny grass heads, identify plant species, and advocate for a better balance of grazed and livestock-free lands.

Volunteers help restore lands and waters in areas impacted by livestock grazing. We pull weeds, protect springs, and plant native species. Join us in the field ›

We team up ranchers, agencies, researchers, and others to minimize grazing pressure on the ground. Learn about our work as a grazing permitee on the North Rim Ranches.

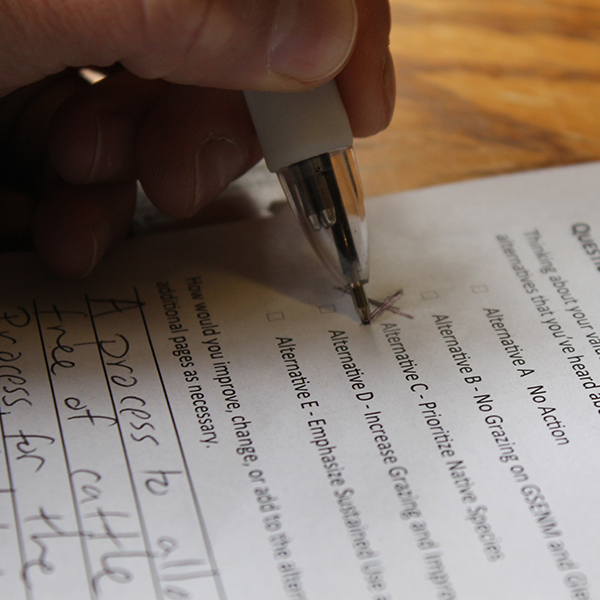

Nearly all of our public lands are open to grazing. We plug into every management process we can to advocate for less grazing across the plateau.

Native plants have evolved to the specific locales in which they grow. They attract colorful polinators like butterflies and bees, provide food and cover for voles, harrier chicks, fawns, and other animals, and help cool the water in streams. Native plants are important components of healthy and balanced natural areas.

On the Colorado Plateau, where rocks outnumber plants, the ground is dry, and water sources scarce, livestock leave big impacts on the land. Native plants wither under the pressure of too many mouths and hooves. We work with ranchers, land managers, and others to study grazing impacts, address problems, and advocate for better grazing policies and management of our public lands.

Fences are just as good at keeping animals out as they are at keeping them in. We use reference areas, which were once heavily grazed, to track the recovery of native species when cattle, deer, elk, and sheep are fenced out. We study the variety of plants that replace non-natives, and count how many of each species we find.

With the help of our herculean volunteers, we remove invasive plants in reference areas across the plateau. Eliminating weed seeds is critical to reverse the trend of invasives, and after years of persistent weeding efforts, we've seen significant decline of non-native species and a glimpse of what healthy public lands could look like.

In the Southwest, cows aren’t grazing in green, bucolic pastures. They roam around parched lands and marginal forests looking for scarce food and even scarcer water. They damage biological soil crusts, erode streambeds, and crush native plants.

We know that cattle graze on the majority of our public lands, but pinning down an exact number is no easy task. We're compiling data from the four Colorado Plateau states — Arizona, Utah, New Mexico, and Colorado — to determine just how widespread cattle grazing is on the Colorado Plateau. Volunteer on the project ›

Want to make a difference on the ground? We have several volunteer trips each year focusing on research and restoration of grazed lands across the Colorado Plateau. Join us in the field!

Speak up for the Colorado Plateau at a moment's notice. We send out timely emails notifying you of opportunities to submit comments, sign petitions, and take other actions on behalf of our public lands.

In 2005, the Trust bought grazing permits on 830,000 acres of public lands north of the Grand Canyon. We work with a ranching family to manage the day-to-day operations of North Rim Ranches. Historically overgrazed, it's the perfect grounds to study and test conservation-based livestock management. Read on ›

We work on the ground, in meeting rooms, and sometimes in court to protect our national forests in southern Utah. Learn more about our conservation-based proposal for the Manti-La Sal National Forest and our restoration work on the Pando Clone, White Mesa Cultural and Conservation Area, and Monroe Mountain.

For 20 years, a landmark deal between ranchers and conservationists protected spectacular side canyons along the Escalante River in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. Now, many have been reopened to grazing. Learn more ›

Public lands, by definition, are open to everyone for a variety of uses. Livestock grazing is the most widespread, as it's promoted and subsidized by federal agencies. Here's how grazing works in the West.

The grazing system in the West is based on a law from the 1930s called the Taylor Grazing Act. It divides millions of acres of public land in “grazing districts,” which are further segmented into “allotments.” Ranchers can apply for permits from the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management to graze livestock on these allotments at a very low cost. Federal grazing fees are currently $1.41 per animal unit month (AUM), an obscure unit of measurement (see jargon list below) that basically means:

States in the Four Corners region charge six to 13 times more to graze on state lands. The formula that determines federal grazing fees is more than 40 years old and doesn't even account for inflation. By subsidizing grazing, the federal government is relying on the public to foot the bill of public lands ranching in the West.

Jargon abounds in the grazing world. Let's break it down:

Allotment: An area of land that ranchers are permited to use to graze their livestock

Exclosures: These are fenced reference areas free of grazing animals that scientists and land managers use to see how the land recovers in the absence of cattle.

Forage: Edible plants that grazing animals eat (example: grasses)

Utilization: This number, often expressed as a percent, describes the amount of plant material that livestock eat compared to how much is available.

Animal unit month (AUM): An AUM is how much food a 1,000 pound cow and a calf (or one horse or 5 sheep) eat in a month.

As 2024 draws to a close, we look back at five maps we created this year that give us hope for 2025.

Read MoreThe new Grand Canyon national monument allows traditional uses like hunting and ranching to continue.

Read MoreYou have the opportunity to comment on how you think some of the most beautiful landscapes in Utah should be managed for the next generation to come.

Read More