Arizona’s attorney general is raising concerns about groundwater contamination at uranium mine near the Grand Canyon.

Canyon Mine (renamed Pinyon Plain Mine) faces questions and opposition on multiple fronts. Most recently, Arizona Attorney General Kris Mayes called on the U.S. Forest Service to take a new look at the risks the controversial uranium mine poses to the Grand Canyon region.

Additionally, the mine’s only approved haul routes to the White Mesa Mill cross the Navajo Nation, which has vowed to stop uranium ore trucks. Revisiting a 2012 U.S. Department of Agriculture financial analysis indicates that altering the mine’s haul route to bypass the Navajo Nation — which generally opposes and regulates uranium transport on its lands — would significantly increase the company’s costs.

And community organizers across the Colorado Plateau continue to protest against the operation of the mine, ore hauling, and operation of the White Mesa Mill, next to the White Mesa Ute community, where Canyon Mine ore and radioactive waste shipments from around the world are sent.

Arizona attorney general warns of “devastating” impacts

In an August 13, 2024 letter, Mayes wrote that the original 1986 environmental impact study for the mine relied on an “outdated, inaccurate understanding” of risks the mine poses to groundwater.

Referring to more recent published science, Mayes warns that if the aquifers below the mine become contaminated, it could have devastating effects, especially on the Havasupai Tribe, which relies on the deep Redwall-Muav Aquifer for drinking water.

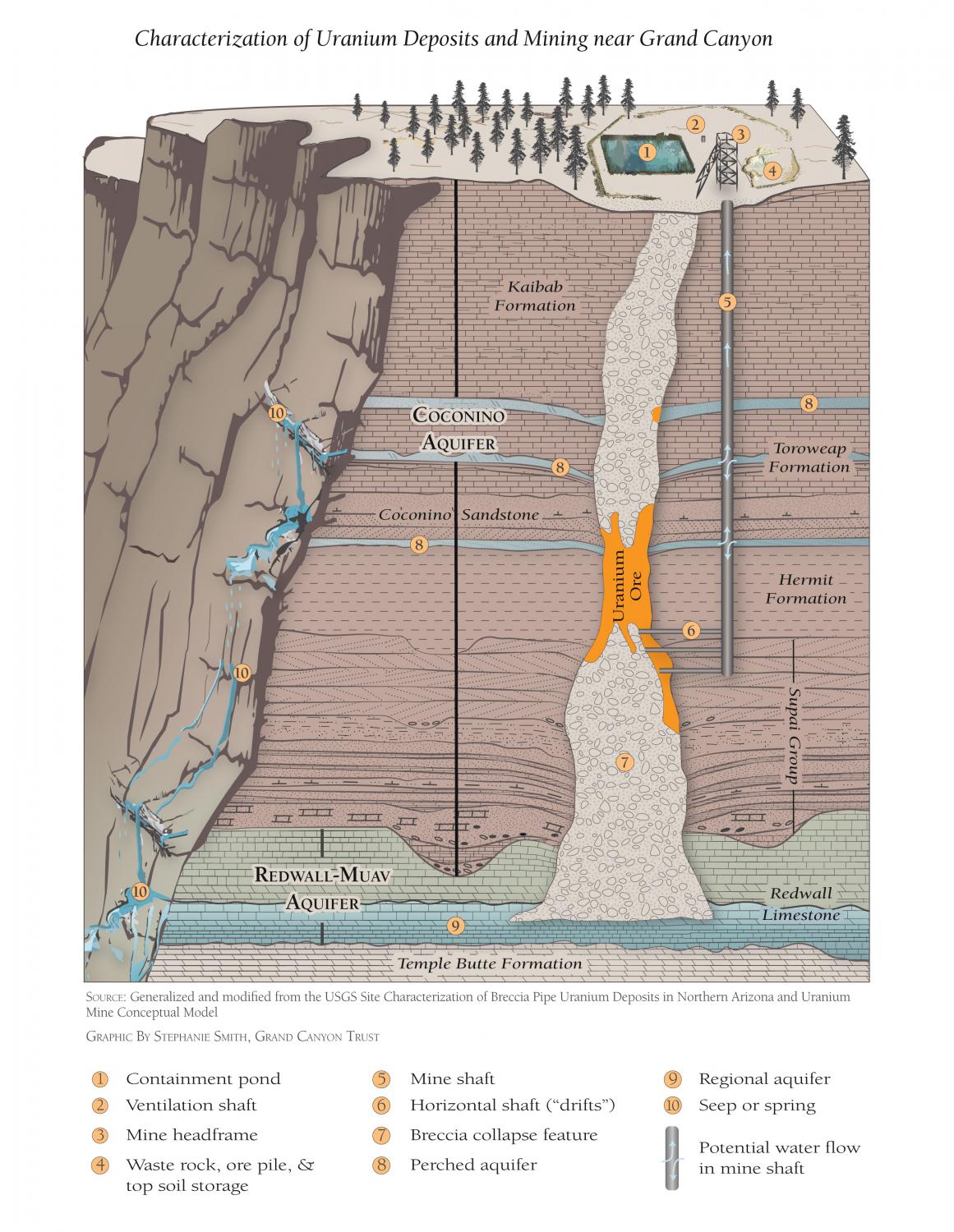

Scientists’ understanding of groundwater in the Grand Canyon area has changed over the last 38 years. Yet regulator reviews and approvals have continued to look to the original analysis. The flow of groundwater in the region is notoriously complex, given the landscape’s many layers of fractured rock. Mayes is asking the Forest Service to take new knowledge into account when determining whether it’s worth the risk to continue to allow uranium mining on national forest lands that are now protected as part of Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni national monument.

The attorney general’s call comes fewer than two weeks after uranium hauling from the mine across the Navajo Nation to the White Mesa Mill in southern Utah sparked protests. A few days after uranium transport began, mine owner Energy Fuels Resources agreed to pause trucking to have discussions with Navajo Nation leadership. Those discussions are ongoing.

Pinyon Plain Mine and risks to groundwater

Mayes points to recent peer-reviewed research that suggests that groundwater systems in the Grand Canyon region are far more interconnected than the 1986 environmental review suggested, making it “highly likely” that contaminants would travel between aquifers below the mine. Research shows that aquifers in the region act as “fluid superhighways,” allowing heavy metals and other contaminants to move between aquifers. Read an interview with the study’s lead author, Dr. Laura Crossey ›

In 2016, miners digging the mine shaft pierced groundwater. As of December 2023, more than 66 million gallons of water had been pumped out of the mine shaft and into an open-air evaporation pond where birds are often observed drinking and bathing. In the last quarter of 2023, when the mine began extracting uranium ore commercially for the first time, levels of uranium, arsenic, and lead in the floodwater pumped out of the mine shaft spiked.

How much would it cost to go around the Navajo Nation?

For now, we still don’t know what will come of ongoing discussions between the Navajo Nation and Energy Fuels, though the Navajo Nation has vowed to stop uranium transport from the mine across its lands, given the devastating legacy the uranium industry has left.

Could haul trucks go around? In theory, they could, though it may require another environmental analysis and it would likely be expensive. The current haul route, from the mine to the White Mesa uranium mill near the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe’s community of White Mesa, is about 300 miles long. Bypassing the Navajo Nation — which is roughly the size of West Virginia — would likely more than double the hauling distance, significantly increasing the company’s hauling costs.

According to a 2012 Forest Service report on the economic feasibility of the mine, called a validity examination, uranium hauling using the current haul route was projected to cost $66 per ton (about $91.59 per ton in today’s dollars), or about 18% of the mine’s total operating costs. The Forest Service has not updated the validity examination in over a decade. But the 2012 cost estimates, even if inexact, leave no doubt that a significant increase in transportation costs would cut into the company’s bottom line significantly.

Concerns from the White Mesa Ute community

So, if the Navajo Nation succeeds in halting ore transportation across its lands, it might not only address the Navajo Nation’s objection to uranium hauling, but also diminish Energy Fuels’ resolve to keep mining. Yet if the company is willing to detour around the Navajo Nation, the environmental, spiritual, cultural, and economic risks the mine poses to the Havasupai people, to the Grand Canyon region’s water, land, plants and animals, and to the state’s tourism economy would remain. As do the concerns of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe and the White Mesa Ute community, whose members live just a few miles down the road from the White Mesa Mill, where the ore is processed, and who are also working to protect their groundwater from the risks of contamination from uranium milling and radioactive-waste processing.

Protests continue, with calls for the mine to shut down

Meanwhile, calls for Canyon Mine/Pinyon Plain Mine and Energy Fuels’ White Mesa uranium mill to close and opposition to ore hauling continue. Community protests are currently being organized for August 24, 2024 against the mine and haul route and October 12, 2024 against the White Mesa Mill.