by Amanda Podmore, Grand Canyon Director

by Amanda Podmore, Grand Canyon Director

Last week, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) took a historic step in recognizing the need for tribal consent for energy projects proposed on tribal lands by halting seven proposed pumped storage hydroelectric projects on the Navajo Nation.

On February 15, FERC issued orders denying permits for controversial dam projects proposed across the Navajo Nation in Arizona, citing the fact that the Navajo Nation had formally objected to each of these projects.

In a reversal of previous policies, FERC announced through these orders that it was "establishing a new policy that the Commission will not issue preliminary permits for projects proposing to use Tribal lands if the Tribe on whose lands the project is to be located opposes the permit." FERC noted that the projects’ developers had not sought or obtained consent from the Navajo Nation for projects on Navajo Nation land that could affect Navajo Nation water, wildlife, and other resources.

The new FERC policy is a historic victory for tribal sovereignty across the United States.

The seven projects that FERC denied were Black Mesa South, Black Mesa East, Black Mesa North, Chuska Mountain, Chuska Mountain North, Western Navajo 1, and Western Navajo 2. Collectively, the projects could have drained up to 687 billion gallons of water from the Colorado River, San Juan River, and groundwater aquifers to initially fill their reservoirs.

View in full screen (suggested for mobile)

The three Black Mesa projects whose preliminary permit applications FERC denied were proposed in 2022 and alone could have used up to 147 billion gallons of groundwater, a staggering amount of water in an arid landscape where tribal water rights have not been fully adjudicated and where many tribal members still haul their drinking water. The Navajo Nation opposed the projects.

According to Tó Nizhóní Ání ("Sacred Water Speaks"), a grassroots group that works to protect Black Mesa’s water from industry use and waste, 19 Navajo Nation chapters (local governments) have also passed resolutions opposing the Black Mesa hydroelectric proposals.

News of the permits being denied came days after the Hopi Tribal Council passed a resolution to ask FERC to change its rules regarding tribal consultation and consent for pumped storage hydroelectric projects on tribal lands. The Hopi Tribe is concerned about the proliferation of proposed hydroelectric projects across the Four Corners region but was not invited to the table to consult when developers filed recent preliminary permit applications on their ancestral lands.

"Our Hopi community is simply asking the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to allow us to be at the table when outside companies want to build projects on our land base, along our waterways, or ancestral spaces that we have been connected to well before the arrival of colonizers," said Craig Andrews, vice chairman of the Hopi Tribe.

The Hopi Tribal Council resolution, passed on February 6, 2024, noted that "FERC's practice of liberally granting preliminary permits without due consideration and its lax requirements for preliminary permit applications are problematic, and long overdue for reconsideration."

The Hopi Tribe is currently reviewing FERC’s new policy on tribal consent and will be speaking with other tribes as potential cosigners on a formal petition urging FERC to establish additional requirements governing tribal consultation and consent before preliminary permits can be issued on tribal lands.

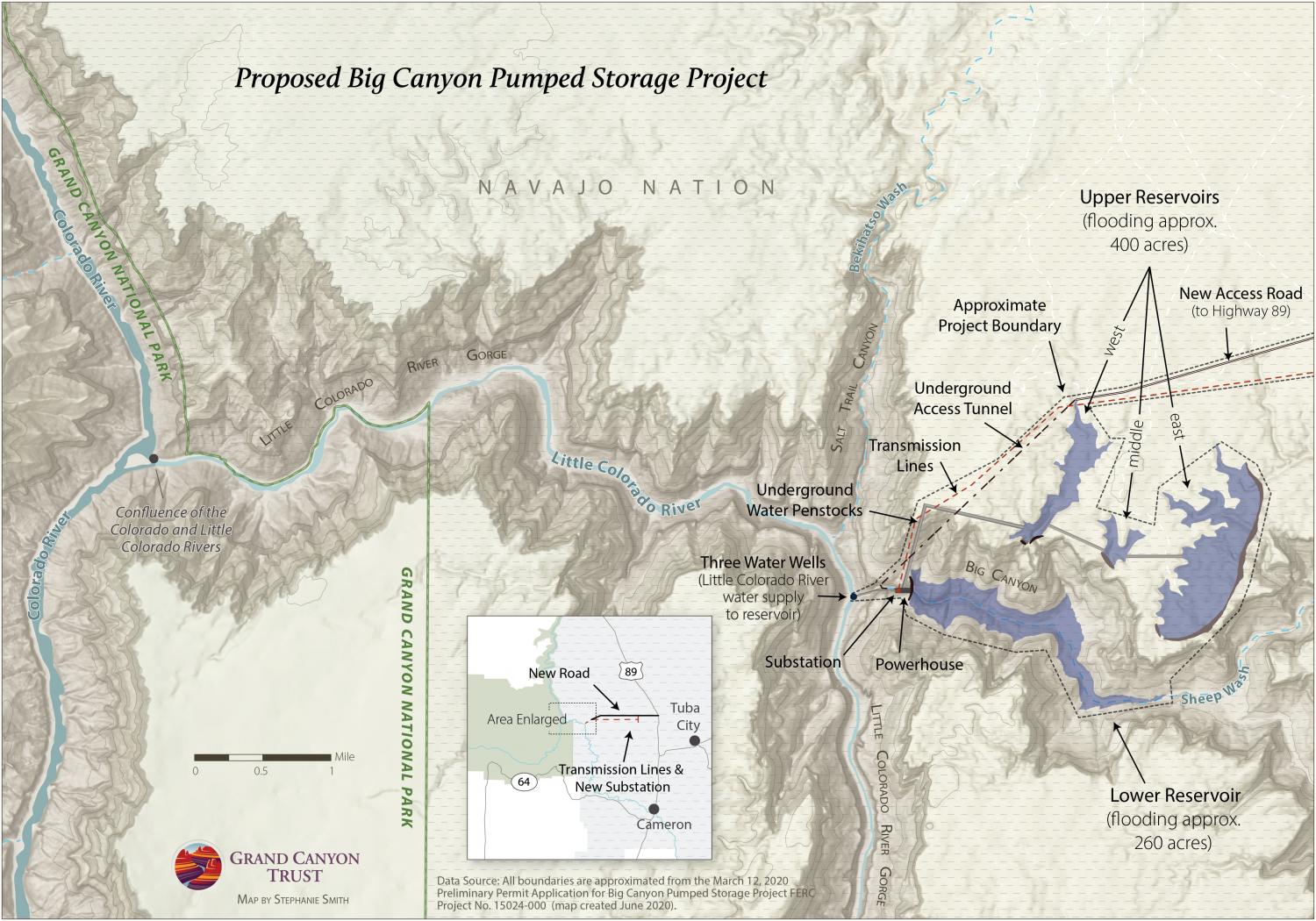

The Big Canyon Dam proposal is one of the projects that the Hopi Tribe along with the Navajo communities, the Havasupai Tribe, and the Hualapai Tribe objected to because of its proximity to cultural sites of deep importance to tribes and Native communities.

The Big Canyon Dam was proposed in 2020 on Navajo Nation land near the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers by an outside developer looking to use pumped groundwater to generate electricity for distant cities. This project was a particular affront to a group of local Diné (Navajo) community members, Save the Confluence, who had successfully fought off a tramway resort proposal nearby.

"We have our umbilical cords buried near the confluence and there are sacred sites there,” said Save the Confluence member Delores Wilson-Aguirre. “Plus the water use for the Big Canyon Dam would not benefit the community right there."

The Navajo Nation Department of Justice has expressed concern that the project could harm land, water resources, fish and wildlife, and cultural resources on the Navajo Nation.

On February 20, FERC announced that in alignment with its new policy, it is opening a 30-day comment period to seek additional input on the Big Canyon Dam proposal. Given the nature of FERC’s rulings last week, this comment period is doubtless intended foremost, if not solely, to provide an opportunity for the Navajo Nation to make a clear statement about whether or not it opposes the permit application for the Big Canyon project.

80% of Arizona voters support Baaj Nwaavjo I'tah Kukveni National Monument, according to a new poll.

Read MoreUtah voters strongly support national monuments in general, and Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante in particular, a new poll shows.

Read MoreA small victory in the legal case challenging Daneros uranium mine, near Bears Ears National Monument.

Read More