by Amanda Podmore, Grand Canyon Director

by Amanda Podmore, Grand Canyon Director

On a particularly windy day this spring, I joined EcoFlight on a flyover of the Little Colorado River. From the river’s headwaters in the White Mountains to its confluence with the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon, we soared over its bends and falls, watching the river — depleted by various human uses — disappear and reappear.

When we reached the site of the proposed Big Canyon Dam on Navajo Nation lands, about five miles from the confluence, we saw no water. Yet somehow, green spring vegetation surrounded the deep Little Colorado River Gorge.

If approved, the Big Canyon Dam would be built in a dry wash and use billions of gallons of groundwater annually to produce electricity for distant desert cities.

It begs the obvious question: is a pumped hydro storage project backed by outside investors in the arid Little Colorado River watershed appropriate? Absolutely not.

A few years ago, a Phoenix-based developer submitted permit applications to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) for three hydroelectric dam projects along the Little Colorado River.

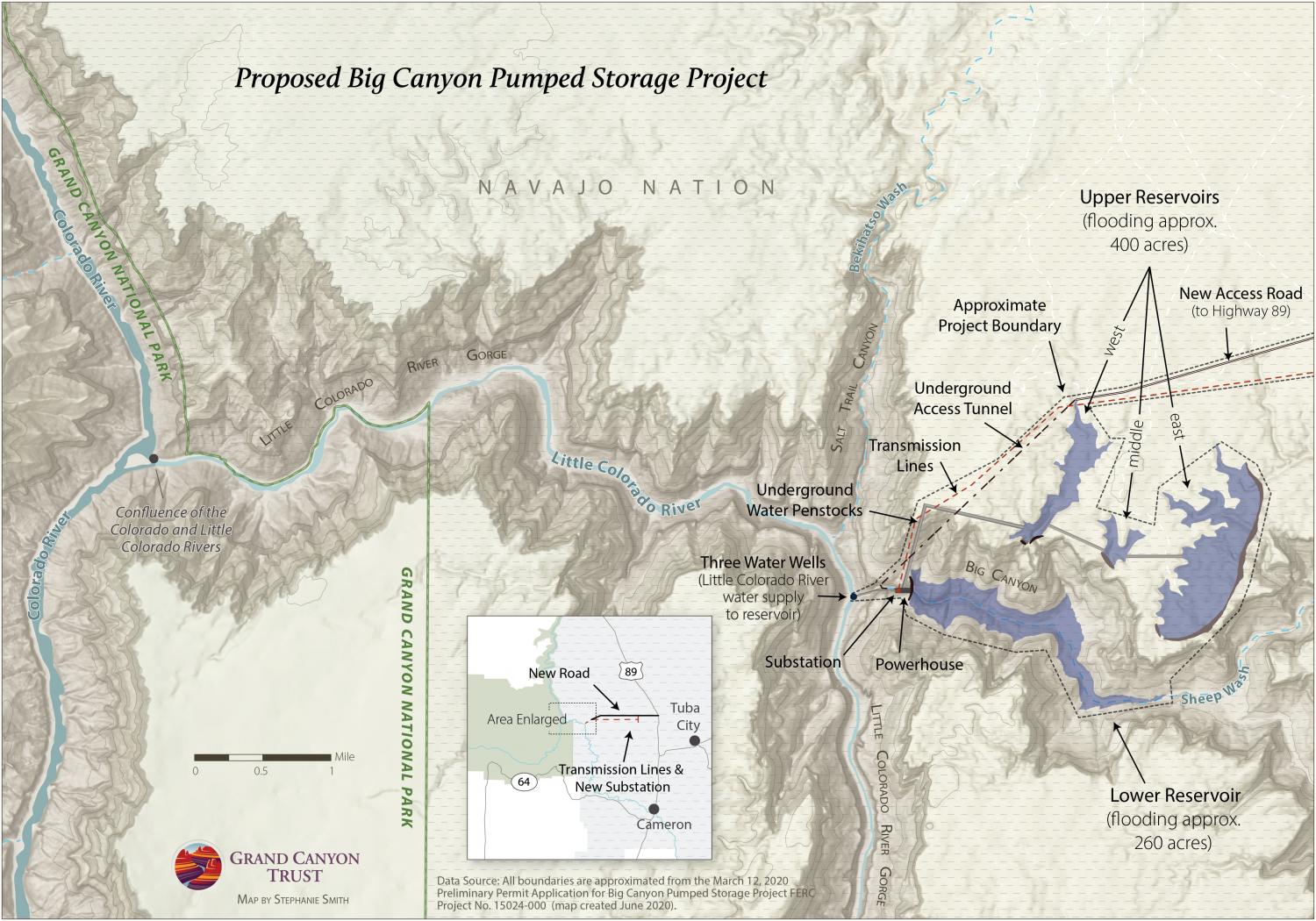

After the company surrendered its preliminary permits for two of the projects in 2021, citing strong opposition from the Navajo Nation and other tribes, it doubled down on its intention to pursue a permit for the Big Canyon Pumped Storage Project.

Big Canyon is a dry tributary of the Little Colorado River. To fill the reservoirs, the developer would need to pump 14.3 billion gallons of groundwater from the local aquifers. These aquifers provide drinking water for local Native communities in the Leupp and Cameron chapters, and support traditional lifeways, like livestock grazing. It also feeds springs in the lower 13 miles of the Little Colorado River known for year-round turquoise flows.

To make matters worse, the proposed Big Canyon storage reservoirs would lose 3-4 billion gallons of water each year to evaporation. The proposal is considered a “closed-loop” project, meaning its water is not sourced from a continuously flowing river. A recent study by the Department of Energy found that closed-loop projects, like Big Canyon Dam, can negatively impact groundwater resources, causing less groundwater to be available for other uses.

The extreme dryness in the Grand Canyon region and across the Southwest is classified as a “megadrought.” It is the driest 22-year period in 1,200 years.

The megadrought has caused Lake Powell levels to drop by 160 feet, the lowest they have been since the reservoir was filled in 1980.

In June, the Bureau of Reclamation underscored the seriousness of the megadrought when it announced that the Colorado River Basin states — Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming — had two months to create a plan to cut water use in 2023 by 2 to 4 million acre-feet (651 billion to 1.3 trillion gallons). For reference, that is more than Arizona’s annual share.

The Big Canyon project would use and waste precious water in a region where summer temperatures soar into triple digits, precipitation rarely falls, and many haul water for their households and livestock.

The Little Colorado River flows through the Navajo Nation. BRUCE GORDON, ECOFLIGHT

The Little Colorado River flows through the Navajo Nation. BRUCE GORDON, ECOFLIGHT

The Navajo Nation imposed water restrictions in the summer of 2021 in response to the ongoing megadrought. Should these water restrictions resume in 2022, it will be all the more important to support local communities in the Cameron and Bodaway-Gap chapters of the Navajo Nation as they work to protect their limited groundwater from guzzling proposals like the Big Canyon Dam.

Big Canyon Dam’s groundwater withdrawals could ultimately diminish local communities’ water resources, alter the blue flows of the Little Colorado River, reduce humpback chub habitat, and threaten the integrity of cultural sites significant to many Native peoples.

The Navajo Nation has not given the developer permission to enter its lands or use its waters, and the Hopi and Hualapai tribes have formally opposed the development as well. These lands are shared cultural spaces, significant to the Navajo, Hopi, Zuni, Hualapai, San Juan Southern Paiute, and many other Grand Canyon tribes.

A local group called Save the Confluence, made up of families who live and graze livestock on the rim above the confluence, is working to protect the lower Little Colorado River from development proposals like Big Canyon Dam and the earlier Escalade tramway that was defeated in 2017.

Save the Confluence is collecting signatures for their petition asking Pumped Hydro Storage, LLC to withdraw its Big Canyon Dam proposal in the lower Little Colorado River. Join us in standing with Native communities and saying no to locally undesired and inappropriate dam proposals on the Little Colorado River.

The Colorado River below Glen Canyon Dam is heating up. Find out why.

Read MoreGroundwater pumping at a uranium mine near the Grand Canyon will affect the canyon's springs, scientists says.

Read MoreArizona Governor Katie Hobbs is the latest elected official to call for an environmental review of Pinyon Plain uranium mine.

Read More