A few times a year, fed by snowmelt and monsoon storms, the normally dry Grand Falls swells into a raging wall of muddy water. The 180-foot seasonal waterfall has become something of a destination for road trippers, van lifers, and influencers in recent years. But for generations, Grand Falls and the Little Colorado River that feeds it have watered livestock, supported medicinal plants, and sustained Native peoples.

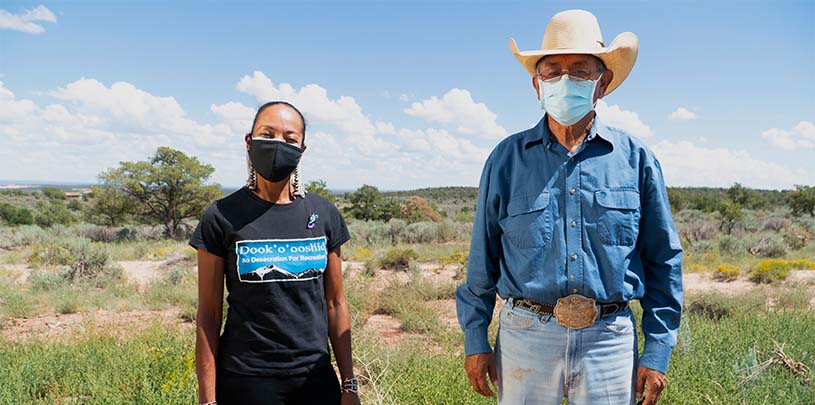

Grand Falls, called “Adahiilíní” in the Diné (Navajo) language, is located on the Navajo Nation in Arizona. For Herman Cody and his niece Radmilla Cody, it is the place they call home.

“We’re all a big family living along that river,” Herman says.

Herman Cody was born in a hogan at his family’s summer home on a windswept mesa several miles north of Grand Falls.

“I was ceremoniously born the Navajo way, out in the middle of nowhere as people say now,” Herman chuckles.

Growing up, he remembers the frequent task of crossing the Little Colorado River with their sheep and cattle. If monsoons came early, fording the river became an all-day task.

“Sometimes the water was a little too deep, but not enough to sweep any goats or sheep downriver. But they’re still skittish. We had a hundred and some sheep, and we practically had to drag every one of them across to the other side.”

The stakes seemed even higher when there was an audience watching the endeavor. Even decades ago, people would come out from Flagstaff to see Grand Falls running. Herman says tourists would stand at the top and watch them work all day, “laboriously dragging each sheep across.”

“One time, my father even shouted to them in Navajo, ‘Don’t just look at us, come down and help us!’ No one did.”

Radmilla Cody, who was raised by her grandmother in the Grand Falls area, recalls spending a lot of time on foot, herding sheep, playing along the banks of the Little Colorado River, and visiting relatives.

“It was a beautiful community,” she says. “It still is.”

Now, Radmilla is sharing the teachings that she learned from her grandmother with her own son.

“He knows the process now, that when we’re near Adahiilíní, we always give our offerings.”

The Little Colorado River is bookended with perennial flows of water, but in its middle stretch across the Navajo Nation, flows shrivel and are dependent on precipitation. For much of the year, the Little Colorado River is a dry, cracked riverbed.

Living along this sometimes flowing, often dry waterway, the Codys have an intimate understanding and respect for water. Every drop counts. Radmilla’s grandmother put empty barrels underneath the roof to collect runoff. During the wintertime, they would melt snow to wash dishes.

Herman says when the river was dry and his family and animals needed water, the only thing to do was grab a shovel.

“How hardy our people were, to spend a whole lot of time out there, just digging, digging down, down, down, until they found water. That’s what it took to live in that area, way back.”

Herman and Radmilla are both musicians. In addition to their own albums, they compose and produce songs together. Their music is always connected to the land and to the sacred elements, says Radmilla.

One of their songs is about the place they grew up. “Honoring the Homeland,” mentions the Little Colorado River several times.

“It’s a beautiful song, and I love singing it,” Radmilla says. “It talks about where we come from at the Adahiilíní.”

Herman also sings a song about the Grand Falls area, entitled “Naasha,” which means “the homeplace.”

Grand Falls is a place that Herman, Radmilla, and their families and neighbors treat with the utmost respect. But most visitors aren’t aware of its cultural significance. Herman says crowds of visitors disrupt the holiness of the area. Weekends during monsoon season are especially bad.

“Monday morning that place is trashed. It’s a whirlpool of garbage, plastic bags, beer bottles,” He says. “It just breaks me to pieces.”

Another problem, according to Herman, is that visitors veer off the main road to the falls and intrude on the lives of the people who live nearby.

“Respect the people who live in the area. They don’t want to be bothered. They don’t want these loud motorcycles or these little vehicles that look like horned toads running all over the place,” he says.

Radmilla recounts similar experiences at Grand Falls, with ATVs zipping around and kicking up dust.

“There’s just no regard for the area. I think my real sincere answer is to just stay away. Leave the Adahiilíní alone. Let it be.”

Guest post by Sarana Riggs

Sarana is from Big Mountain, Arizona, and is a member of the Navajo Nation. As an independent consultant, she educates about and advocates for cultural and environmental protections for all Indigenous peoples in the Southwest.

The Colorado River below Glen Canyon Dam is heating up. Find out why.

Read MoreGroundwater pumping at a uranium mine near the Grand Canyon will affect the canyon's springs, scientists says.

Read MoreArizona Governor Katie Hobbs is the latest elected official to call for an environmental review of Pinyon Plain uranium mine.

Read More