by Sarana Riggs, Grand Canyon Manager

by Sarana Riggs, Grand Canyon Manager

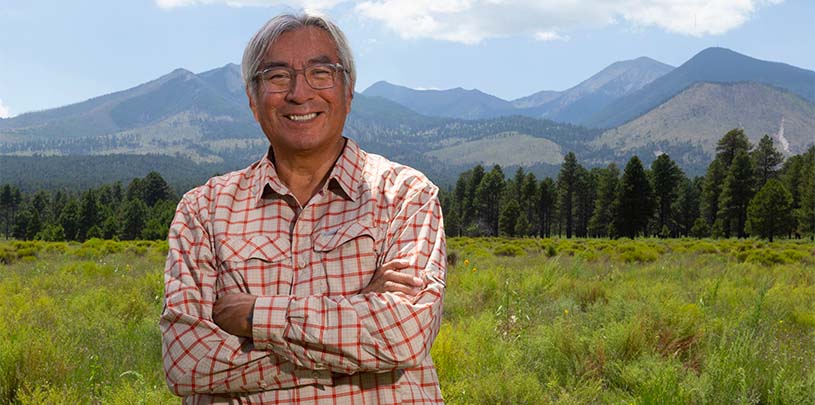

Jim Enote, a Zuni farmer, has been planting seeds and growing crops for 64 consecutive years. His grandparents put seeds in his hands when he was still tied to a cradleboard, and he’s been planting ever since. Some years bring late frosts, other years, drought. This year, the artesian spring that waters Enote’s field filled with sand and mud from heavy flooding.

“When I stand in my field that I’ve just planted, and it’s hot and dry, and the corners of my mouth are cracked, I’m wishing for rain. Not only for me, but for the plants that are like my children,” Enote says. “There’s nothing better than a nice, long, gentle rain. Water is certainly life.”

DEIDRA PEACHES

DEIDRA PEACHES

Enote says that the world began for the Zuni people at a place called Chimik’yana’kya dey’a, which most people know as Ribbon Falls, in the Grand Canyon.

“That is the place where the Zuni people emerged from beneath the surface of the Earth. After many years living in the Grand Canyon, we explored the tributaries of the Colorado River, including the Little Colorado River, finally to the Zuni River. Then we settled in Zuni, where we are now.”

He explains, “The Little Colorado River is like an umbilical cord that connects us back to our emergence place, the Grand Canyon.”

Growing up, Enote’s grandparents told him that if he walked out of their front door and followed the Zuni River downstream, he would eventually reach the Grand Canyon.

“One of my earliest memories is being told that the river takes us back to where we came from,” he says. “All the tributaries nourish and contribute to the place where we began.”

In the old days, Enote says Zuni people would literally walk from the Zuni River, to the Little Colorado River, into the Grand Canyon as a pilgrimage.

“Today, we don’t have that liberty. Lands have been privatized and settled.”

Enote likes to think of the landscape like a living map, where all the mountains, and rivers, and canyons are related to each other.

“It is not just a river, it is in the context of a larger landscape — the mountains, the volcanoes, smaller tributaries, and villages. The river is representative of broader contextual things in our history,” Enote says.

The Little Colorado River also gives life to many in the region, Enote explains. Birds use it as a stopover on their migration routes. Endangered fish spawn in its warm waters. Alpine flowers grow along the riverbanks high in the headwaters of the White Mountains, and desert cottonwoods offer shade to bighorn sheep and other creatures.

“It’s alive. It may appear dry at times, but in its ephemeral way it comes to life again. It awakens and it dries. And there’s something really beautiful about that,” Enote says.

Within Enote’s lifetime, he’s seen the Little Colorado River get drier and drier. The river flows less reliably than it used to. When Enote’s ancestors experienced changing climates in the past, they were able to migrate to greener pastures. Now, that’s not the case, Enote says.

“It’s not like we can pick up entire tribal nations and be climate refugees. And the same applies to the infrastructure of cities.”

According to Enote, if we’re going to change the course of a drier world, than we have to think about future generations.

“Our ancestors have been monitoring this Earth for over 600 generations. And they made choices, while thinking about us today. We have to do something now to address climate change, and we have to do it with a new morality and a concern for the future.”

80% of Arizona voters support Baaj Nwaavjo I'tah Kukveni National Monument, according to a new poll.

Read MoreThe Colorado River below Glen Canyon Dam is heating up. Find out why.

Read MoreGroundwater pumping at a uranium mine near the Grand Canyon will affect the canyon's springs, scientists says.

Read More