Last December, in a mining-industry lawsuit we helped fend off, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a decision made by former Interior Secretary Ken Salazar to ban new uranium mines and claims for two decades on about a million acres around the Grand Canyon. It was a major victory for tribes, sportsmen, conservation groups, and members of the public who want to see the Grand Canyon protected from the risks of uranium mining. The court’s ruling doesn’t prevent the Trump administration from attempting to lift the ban. But it does mean that the ban is legal and remains intact, barring any executive or legislative action to remove it.

This lawsuit began immediately following the 2012 announcement of the 20-year ban. In the suit, the mining industry attempted to argue that the mining ban was adopted improperly — an argument that was first rejected by a federal district court in Arizona in 2014. The 9th Circuit’s recent decision affirms that outcome across the board. Unless the Supreme Court takes the case, the 9th Circuit’s decision puts an end to this long-running lawsuit.

Executive Order 13783 resulted in a November U.S. Forest Service recommendation that the administration review the Grand Canyon mining ban as a way to lift burdens on domestic energy development. More recently, Executive Order 13817 resulted in the inclusion of uranium on a draft list of 35 “critical” minerals, access to which the administration plans to prioritize. This means that for as long as uranium is listed, it will be the policy of the federal government to identify new sources of uranium, increase activity at all levels of the supply chain, “including exploration [and] mining,” and streamline leasing and permitting processes to expedite exploration, production, processing, reprocessing, recycling, and domestic refining of uranium.

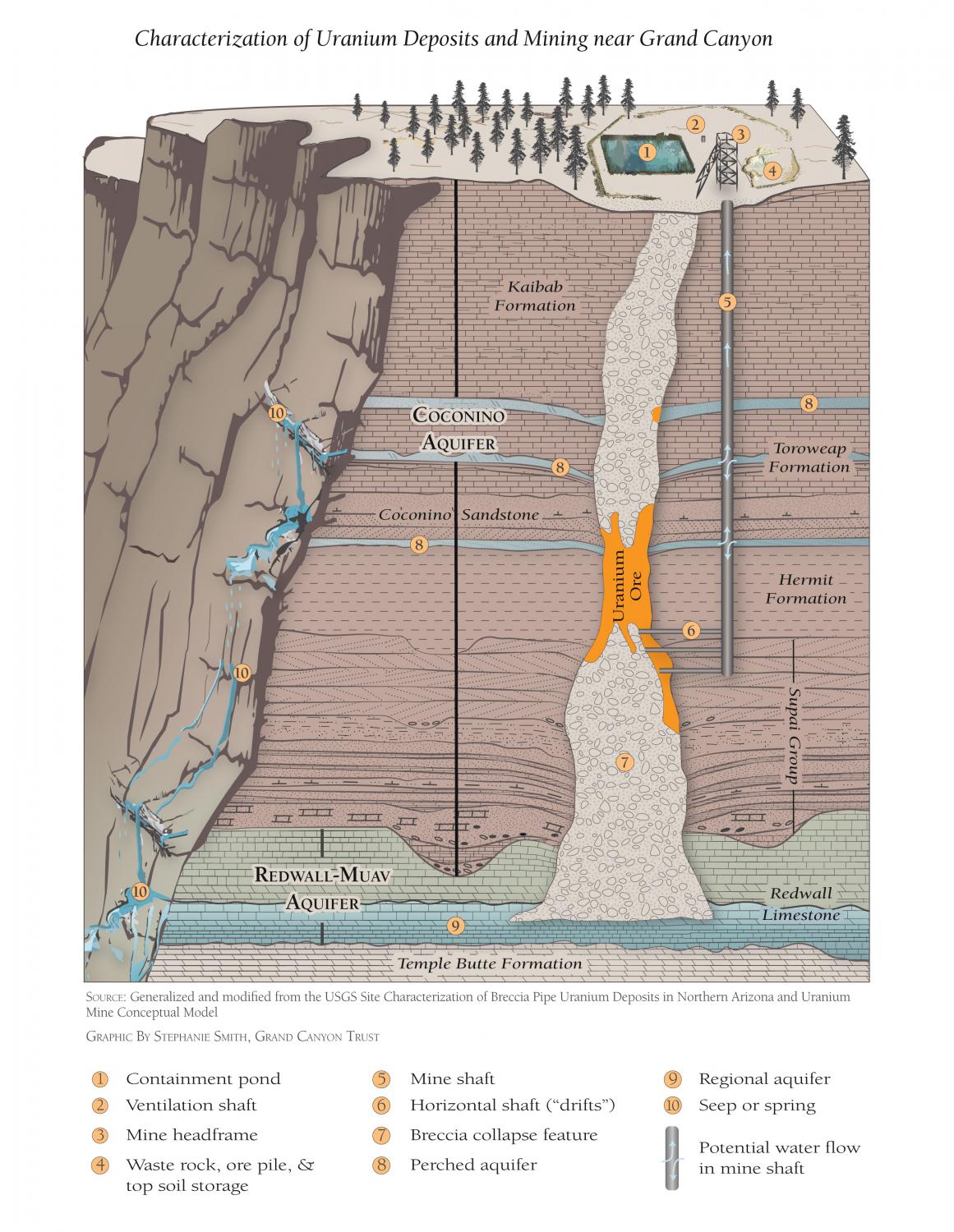

To fully understand what’s at stake, it’s worth remembering that the ban was implemented after an extensive review process that took more than two years, involved nearly 300,000 public comments, and relied on the best available peer-reviewed science — science that indicated that available data on pathways for contamination in the region are “sparse…and often limited” and that more research is needed to understand groundwater flow paths and the potential for uranium mining to cause contamination. The mining ban was meant to provide more time to chip away at these unknowns.

The necessity of the ban is compounded by other factors too. In the six years since the ban was put in place, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has been deprived funding from Congress for the research that is needed. With no obligation for uranium mining companies to assist financially, far less research has been done at this point than is needed to draw any of the necessary conclusions for the mining ban to be lifted. If that weren’t bad enough, President Trump's newest budget proposal would entirely eliminate funding to the USGS for Grand Canyon hydrology research.

The necessity of the ban is compounded by other factors too. In the six years since the ban was put in place, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has been deprived funding from Congress for the research that is needed. With no obligation for uranium mining companies to assist financially, far less research has been done at this point than is needed to draw any of the necessary conclusions for the mining ban to be lifted. If that weren’t bad enough, President Trump's newest budget proposal would entirely eliminate funding to the USGS for Grand Canyon hydrology research.

Lastly, the northern Arizona economy is driven by outdoor recreation, travel, and tourism, not by uranium mining, which generates $0 in royalties for taxpayers and is capable only of providing a small number of temporary jobs. According to the Arizona Mining Association, all types of mining (of which uranium is a small part statewide) provided 195 jobs in Coconino and Mohave counties in 2014, the most recent year for which statistics were available. Canyon Mine, south of Grand Canyon National Park, is expected to temporarily provide up to 60 jobs at peak operation. Lifting the ban only puts the region’s real economic driver at risk.

The Grand Canyon Trust and our partners are keeping close track of the administration’s movements on this issue and are proactively working to defend the ban and ensure that the hundreds of thousands of people who support protecting the Grand Canyon are apprised of threats to the mining ban.

This winter, the Trust traveled to Washington D.C. where, alongside representatives of Trout Unlimited, the Arizona Wildlife Federation, and the Havasupai Tribal Council, we met with leaders of federal agencies and members of the Arizona congressional delegation to explain that lifting the ban would do little to assist domestic energy and economic development, and place at risk our regional economy, tribal and water resources, and, of course, a world heritage site — the Grand Canyon itself.

Amber Reimondo directs the Grand Canyon Trust's Energy Program.

Amber Reimondo directs the Grand Canyon Trust's Energy Program.