BY TIM PETERSON

This winter marked tough times for Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments, but time is relative here. Bears Ears holds a record of more than 13,000 years of human history, from the hunters of the last mammoths to roam the Colorado Plateau to the present day. Time in Grand Staircase is deeper still. The monument is a treasure trove of geology and dinosaur fossils. More than two dozen new species of dinosaur have been discovered here since the monument’s 1996 designation, and 2017 witnessed the unearthing of the most complete juvenile tyrannosaur skeleton ever recovered.

Grand Staircase is a volume in the encyclopedia of Mother Earth, her bones laid bare for all to see in her stunning rock formations, and she has so much more to teach us about the ancient climate and the creatures that lived and died before humans.

From lying in wait for the precise moment to strike just behind a mammoth’s shoulder, to waiting for fickle rains to grow fields of corn, squash, and beans, to working some 80 years to see a cultural landscape protected under the laws of modern America, Bears Ears is still teaching and testing our patience.

Showing profound disrespect for indigenous people, Trump’s proclamation for Bears Ears attempted to reduce the scope of Native American collaborative management to only one of the two broken monument units. He renamed the unit “Shash Jáa (sic),” the Navajo words for Bears Ears, dishonoring the historic intertribal partnership among the Hopi, Navajo, Ute, Ute Mountain Ute, and Zuni nations that advocated for the monument’s creation.

That day in Salt Lake City, President Trump launched the most devastating attack on protected public lands in American history, removing some 2 million acres from national monument protections. Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke has claimed since that “there isn't one square inch of Bears Ears that was removed from any federal protection." But that simply isn’t true.

National monuments are managed to prioritize the protection of important historical and cultural sites, geology, and fossils above all other resource uses so as to keep them unimpaired by consumptive activities like mining, drilling, and logging. Absent intervention by the courts, when national monument status is removed, the lands revert to the status they held before designation, and the protective tent that prioritizes protection of the monument’s riches is taken down, leaving the land vulnerable to damage from destructive uses.

When Trump removed 2 million acres from national monument status that day, he tore away at the overarching reasons for which the monuments were designated.

President Trump has said about bronze Confederate monuments that he’s “sad to see the history and culture of our great country being ripped apart.” But his attempts to eviscerate national monuments do more than that — he’s trying to tear apart not just our history, but our prehistory as well.

The Antiquities Act of 1906 gives presidents one-way authority to create, but not to shrink or eliminate national monuments.

National monuments have been shrunk before, but most often they were altered to correct mistakes made by early mapmakers. Other monuments were cut dramatically, like Mount Olympus National Monument in Washington state, but only because there was an urgent national need for timber during World War I. Mount Olympus was later expanded and re-designated Olympic National Park after the war.

In the interim, Congress passed the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976, in which Congress expressly reserved the power to modify or revoke withdrawals for national monuments. Previous reductions were not challenged in the courts, and no president had acted to reduce a national monument since Congress clarified its authority, so there is no precedent for Trump’s actions under current law.

Because of this, the five tribes of the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition immediately filed suit in federal court in Washington D.C. on Bears Ears. The Grand Canyon Trust and our partners also quickly filed lawsuits on both monument reductions, seeking to see the original monuments restored. Now the courts are teaching us patience. As of this writing, three separate complaints on Bears Ears and two on Grand Staircase have been consolidated. The Department of Justice has filed motions to transfer the cases to Utah, a venue the government probably sees as more favorable to Trump’s arguments. A ruling on these motions is expected any day. And wherever the case lands, when the court reaches the merits, we believe Trump’s actions were so offensive to the law that the courts must overturn them.

In a seeming admission of the president’s lack of authority, as the ink dried on Trump’s proclamations, two Utah members of Congress introduced bills to codify the overhaul of Bears Ears (H.R. 4532) and Grand Staircase (H.R. 4558). Both go further than just cementing Trump’s unlawful action. They create new mechanisms in law to turn management authority over to the very state and county officials who sought to eliminate the monuments entirely, bringing them one step closer to their goal of transferring public lands to state ownership.

Both bills face a tough fight and stiff opposition from Native American tribes, conservationists, sportsmen, and outdoor recreationists. Should the bills clear the House of Representatives, there is hope that the more deliberative Senate will hold them until the courts decide on the legality of Trump’s proclamations, appropriately respecting and upholding the authority of the judicial branch.

We continue to support the tribes defending Bears Ears, and to do all that we can in the media, the courts, and the halls of Congress to defend both monuments. They are far too important for too many reasons to let down our guard now.

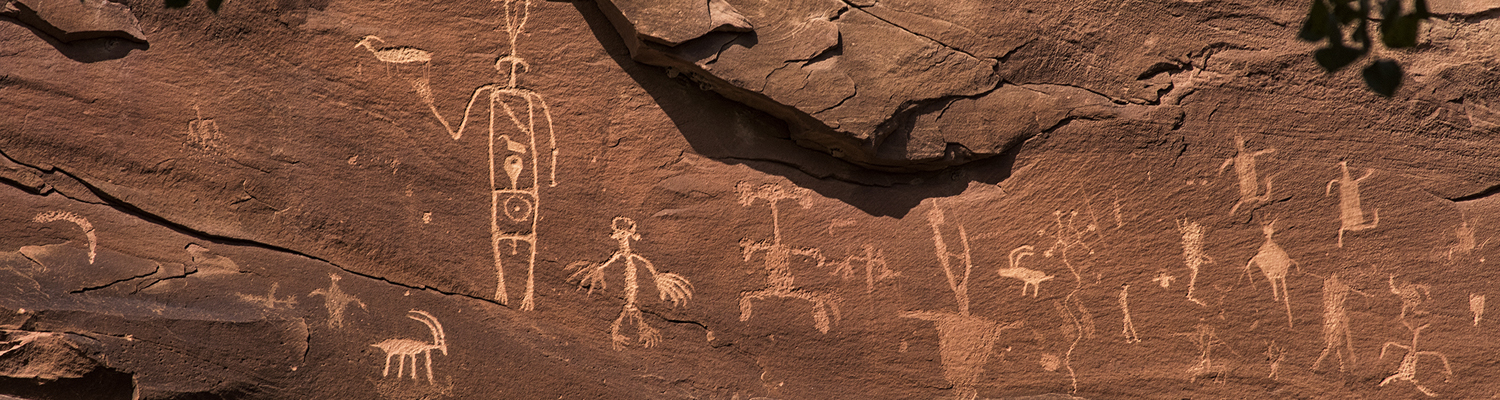

Indigenous people have known these places as home for hundreds of generations, and they know them today from their own cosmology, their oral histories, and the rites of pilgrimage and ceremony still practiced there as they have been for far longer than the United States has been a nation. This is patience. In the words of Hopi Vice Chairman Clark Tenakhongva: “Our documents are the petroglyphs written in stone. The U.S. government’s are written on paper. Tell me which holds water ― paper or stone?” We’re betting on stone.

Tim Peterson directs the Grand Canyon Trust’s Utah Wildlands Program.

Tim Peterson directs the Grand Canyon Trust’s Utah Wildlands Program.