by Travis Bruner, Arizona Forests Manager

by Travis Bruner, Arizona Forests Manager

The Mogollon Rim ponderosa pine belt forms the southern edge of the Colorado Plateau. It is a stunning landscape home to hidden canyons, springs, and myriad life forms. But Arizona’s forests are also a huge source of fuel, and, if sparked, the world’s largest ponderosa pine forest could be set ablaze.

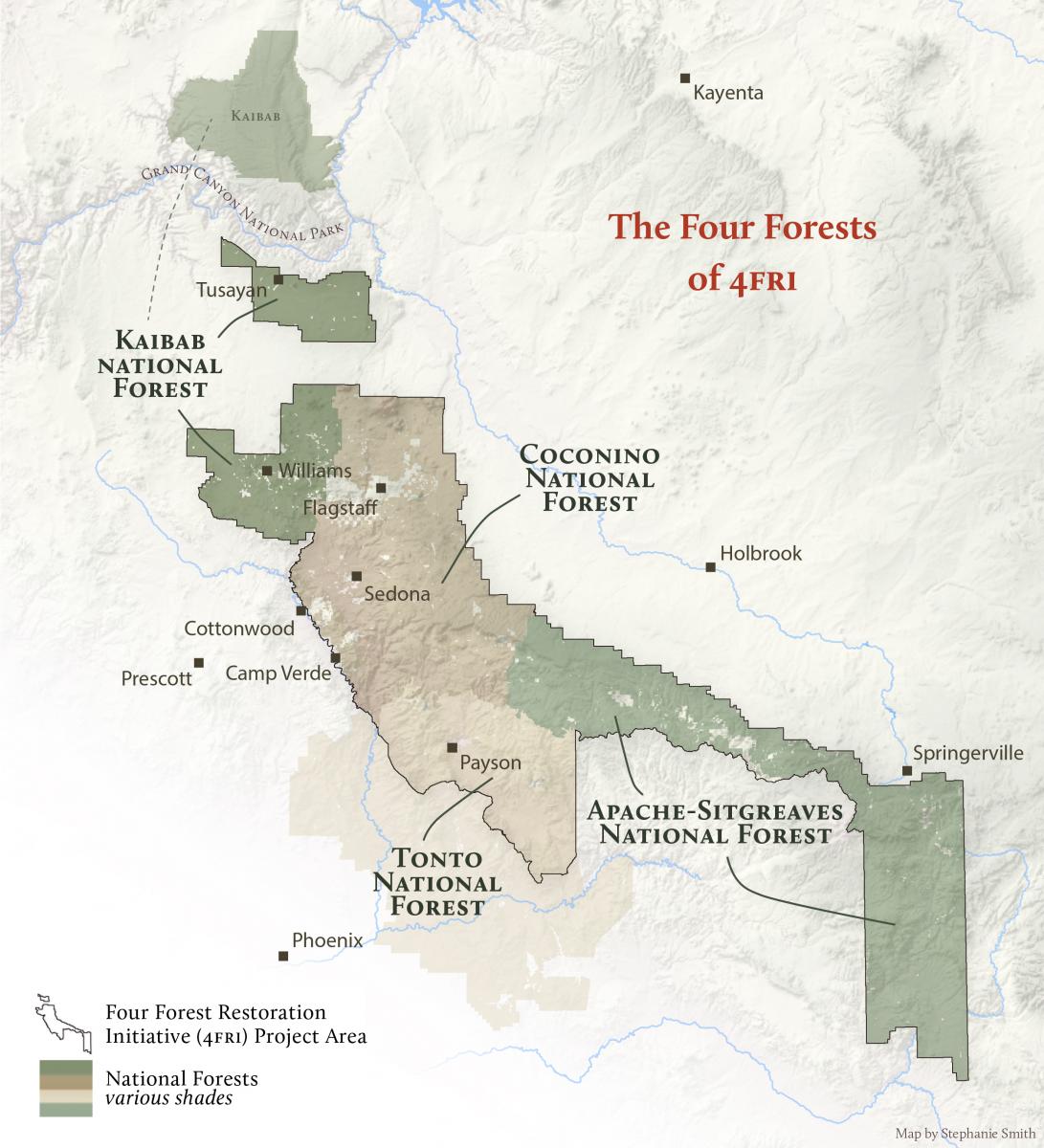

For more than five years, the Trust has been working closely with the Forest Service and more than 30 other organizations to reduce the threat of unnaturally severe wildfires and to restore broader-scale, lower-intensity fire across 2.4 million acres of the Mogollon Rim. The Four Forest Restoration Initiative (4FRI) is the largest forest restoration project in the nation and is unprecedented in it’s geographic scale, collaborative involvement, and inclusion of citizen science.

Since the 1990s, enormous and severe forest fires have become more common in this region, degrading municipal watersheds, destroying houses and buildings, endangering human lives, and costing taxpayers millions of dollars. In 2002, the Rodeo-Chediski Fire in the White Mountains burned 468,638 acres and resulted in over $308 million in property loss, fire suppression, and emergency stabilization costs. The Wallow Fire, in 2011, burned 538,049 acres and fire suppression costs alone exceeded $80 million. During 2015, the federal government spent over $2 billion fighting fires on Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and other federal lands.

Beyond these human-centric concerns about property and money, this new type of fire presents serious concerns for the ecological health of our forests. Scientific and historical research indicates that the severity of these fires far exceeds that of fires prior to Euro-American settlement. Clear-cutting transformed what was a wide array of tree ages and sizes into a more uniform structure less supportive of wildlife and plant biodiversity. Domestic livestock overgrazing removed vegetation and diminished the frequency of understory fires that would replenish grasses, reduce small tree density, and restore nutrients to the soil. Combined with fire suppression and climate change, these logging and grazing practices loaded northern Arizona forests with dense stands of small-diameter trees, primed to ignite, climb up to the canopy, and burst into landscape-scale crown fires.

During the late 1990s and early 2000s, scientists, advocates, industry representatives, and government agencies began to see the need for ecologically sound small tree thinning and prescribed burning. During the mid-2000s, many of these groups starting coming together to share ideas and work toward common goals at the landscape scale. The parties understood the need for such projects to restore wildlife habitat and biodiversity, protect watersheds, adapt to climate change, safeguard communities, provide economic opportunities, and improve recreational opportunities. This convergence of diverse interests created the space for a discussion about how to translate these ideas into action on the ground.

And that discussion found form in 4FRI.

In May 2009, we participated in the first stakeholder meeting in Flagstaff, and the name “Four Forest Restoration Initiative” was born. A bill passed that year established the Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program, which provided the financial and administrative support required to move forward with such an ambitious landscape-scaled forest restoration initiative. In June 2010, 28 organizations signed the 4FRI Stakeholder Group Charter, which articulated the mission of the group and the steps required to accomplish that mission.

During the five years following the initial support from the Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program, the stakeholders worked tirelessly to find consensus on issues like large tree retention, protection of wildlife habitat, spring and stream restoration, and new aspen growth. By 2015, stakeholder group positions were translated through the filter of the Forest Service and relevant federal public land law into a plan for action. That work is presently moving forward with constant engagement from stakeholder organizations and the public in general.

Right now, we’re working in phase one of the project to up the pace of 4FRI on all fronts and make sure that the mechanical thinning, prescribed burning, and other restoration actions outlined in the Environmental Impact Statement take place across the 586,000 acres of forest lands. Our leadership will be essential in the coming months and years, and the Trust’s reputation as a trusted, knowledgeable, and fair-minded voice will continue to bolster our ability to work with all the involved stakeholders.

Spring and stream restoration projects are starting to hit the ground, with the help of volunteers at the Trust and other nonprofit organizations. These citizen scientists assist the Forest Service with inventory and monitoring at springs and streams throughout the 4FRI footprint. Challenges remain related to thinning and burning operations, but we expect to see more progress in the coming months.

The Rim Country Project, which is the second in the 4FRI area, will lay out plans for restoration on an additional 1.24 million acres in the Apache-Sitgreaves, Tonto, and Coconino National Forests. We expect to see a draft of the full Environmental Impact Statement for this project in the spring of 2017, the final in late 2018, and a final decision in early 2019. With significant issues related to thinning, burning, grazing, and restoration of springs, stream, riparian areas, and aspen on the table, the Rim Country Project’s unfolding promises to sprout some interesting discussions during the coming months. We’ve started on-site conversations and will be working to find consensus around approaches in the project area, particularly regarding the retention of large trees.

Our 4FRI volunteer trips have wrapped up for the season, but keep an eye on our events page for future opportunities ›

Comments (3)

Leave A Comment