Pinyon jays recover their cached pine nuts about 95% of the time.

If you wander about in the pinyon-juniper woodlands of the Colorado Plateau, you may find the weighty silence suddenly interrupted by a flock of blue birds, leap-frogging each other from tree to tree and sending out strange quavering caws (which sound like this). This is the call of the pinyon jay, a fascinating bird that shares its name with the pinyon pine. These two species have also shared a long evolutionary dance of mutual dependence, yet both are facing unprecedented threats.

Pinyon jays rely on pinyon pines for food

Pinyon jays inhabit home territories year after year, and rely on nutrient-dense pinyon pine nuts for food. When there is a surplus of pine nuts, the jays cache them in the ground for later. Researchers have found that the jays have an uncanny ability to recall their cache locations — they successfully relocate their cache about 95 percent of the time. The 5 percent failure rate turns out to be advantageous for the pinyon pines. Nuts remaining in the soil can germinate as new trees.

The pinyon pines, however, are not merely passive subjects in this story. The trees do not produce nuts every year, and over time they have synchronized their seed production, resulting in what is called a bumper crop. So many pinyon trees producing massive amounts of pine nuts at the same time overwhelms the nuts’ consumers, including pinyon jays. If a tree produces nuts at a different time than other trees, most of its nuts will likely be consumed, putting the tree at a reproductive disadvantage. This leads to more and more synchronization of pine nut production over time.

Pinyon jays help pinyon pines spread their seeds

Although pinyon pines overwhelm the pinyon jay by producing a bumper crop, they also rely on the bird to spread their seeds across the landscape. And the pinyon jays are so keen on pinyon pine nuts as a food source that green pinyon cones stimulate the growth of reproductive glands in the birds in preparation for breeding. This relationship of mutual dependence took ages to evolve.

Destroying pinyon-juniper forests puts pinyon jays at risk

The pinyon jay population has shrunk by an estimated 85 percent since 1970, and another 50 percent of the remaining population is expected to be lost by 2036. Meanwhile, pinyon pines are especially susceptible to droughts associated with climate change.

Researchers believe a major reason for pinyon jay decline is the widespread destruction of pinyon-juniper forests on public lands. In some cases, these forests have been obliterated and then replaced by non-native grasses seeded for cattle forage, which essentially amounts to farming your public lands for private benefit. Additionally, much of the tree removal has taken place where pinyon-juniper woodlands meet lower elevation sagebrush or grasslands. This happens to be where pinyon jays tend to nest, forage, and cache food.

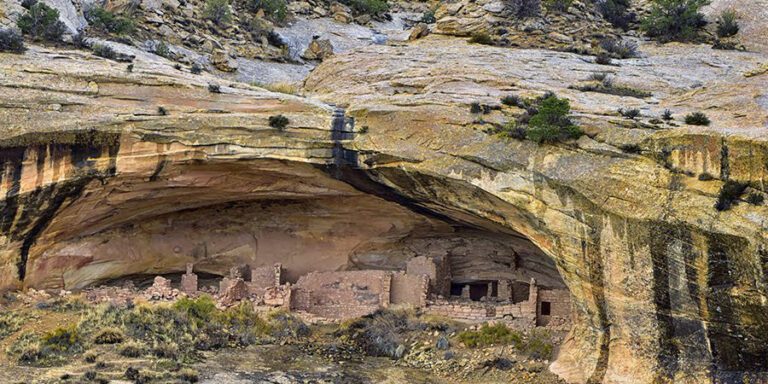

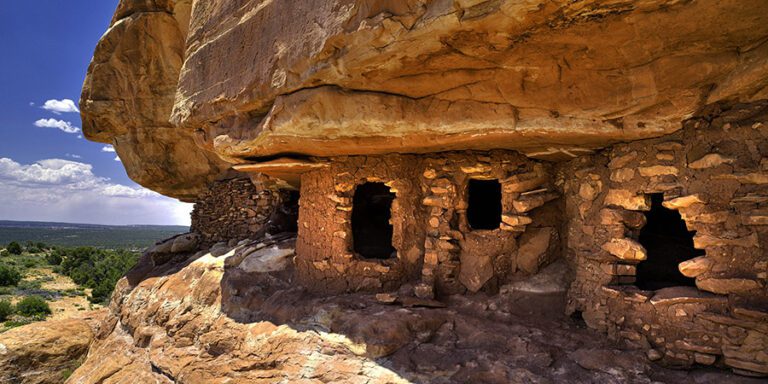

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument forests targeted

Despite the bleak outlook for pinyon jays, federal agencies that manage our public lands are proposing to reduce thousands of additional acres of pinyon-juniper woodlands to woodchips. For example, the Bureau of Land Management is proposing to cut down a great deal of pinyon and juniper on well over 100,000 acres in and next door to Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument alone. These proposals could lead to widespread removal of old-growth trees that can be centuries old, and fail to address how livestock grazing and suppressing the natural cycle of wildfire affect the land.

The pinyon jay is just one species among many that are affected by how we humans decide to use and manipulate the land of the Colorado Plateau, but it highlights the fragile evolutionary relationships that we may be jeopardizing with our land-use decisions.

The Grand Canyon Trust is advocating for a more science-based approach to the management of pinyon-juniper woodlands, which honors the long evolutionary history that created the beautiful interrelationship of pinyon jays and pinyon pines, among many others. Our species must seek to ensure that stories like this one are allowed to continue to develop alongside us.