Commission halts developer’s attempt to dam Big Canyon, near the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado rivers.

On April 25, 2024, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) struck down a plan to dam Big Canyon, a threat that had loomed over the Little Colorado River and the Grand Canyon region for years.

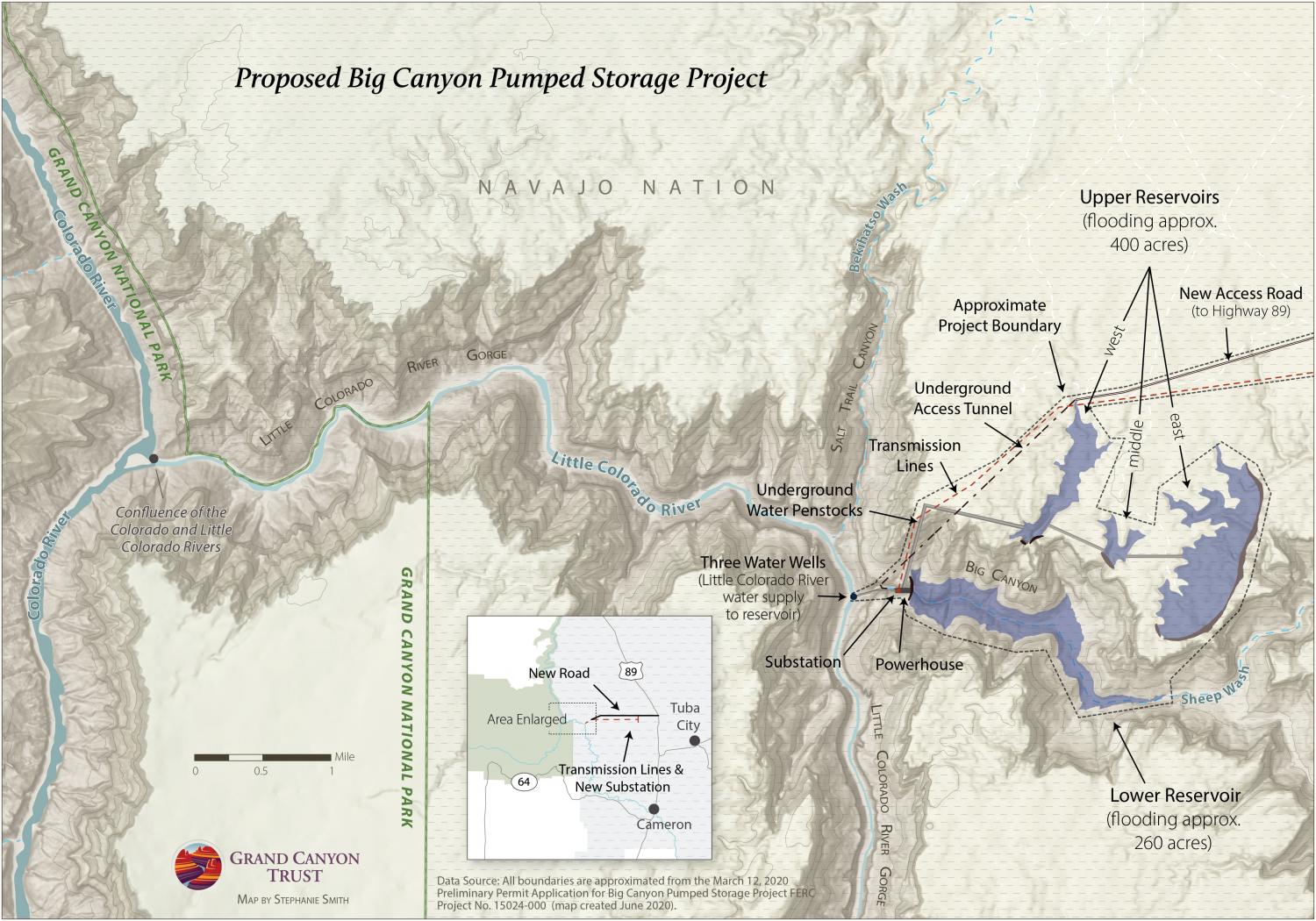

The project, proposed in 2020 by Phoenix-based developer Pumped Hydro Storage LLC, would have dammed Big Canyon, a tributary canyon to the Little Colorado River Gorge, mere miles from Grand Canyon National Park.

The developer’s permit application proposed pumping billions of gallons of groundwater to fill massive reservoirs. This pumped would have endangered seeps and springs that feed the Little Colorado River upstream of its confluence with the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon.

Federal Energy Regulatory Commission reaffirms commitment to respect tribal sovereignty

In striking down the developer’s permit application, the commission reaffirmed its commitment not to issue preliminary permits for hydropower projects on tribal lands without the consent of the tribe on whose land the project would be built. The commission noted: “because the proposed project would be located entirely on Navajo Nation and the Nation has stated that it opposes issuance of the permit, we deny the application.”

Tribes strongly opposed the Big Canyon Dam

The Navajo Nation, the Hopi Tribe, the Hualapai Tribe, and many others strongly opposed the project starting in 2020.

In March 2024, the Navajo Nation submitted additional comments to the commission strongly condemning the project and making clear that “the Little Colorado River and surrounding features hold significant cultural and historical value that must be recognized and preserved,” and that disturbing the area could harm culturally-important plant, fish, and wildlife species.

Of particular concern is the confluence of the Colorado River and Little Colorado River, where the two rivers come together in the heart of the Grand Canyon. The confluence is sacred to many tribes in the region. And it has long been the target of outside developers looking to profit from the area’s natural beauty, hatching plans for everything from hydropower dams to gondola tramways.

The confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado rivers, in the Grand Canyon. RICK GOLDWASSER

The confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado rivers, in the Grand Canyon. RICK GOLDWASSERCommunity opposition to Big Canyon Dam

Many Native-led grassroots groups have worked to oppose hydropower projects in the region, including Save the Confluence and Tó Nizhóní Ání (“Sacred Water Speaks”).

“For as long as we remember living near the canyon and herding sheep, we always considered the area sacred,” explained founding Save the Confluence member Delores Wilson-Aguirre in a comment letter to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. “We offered our prayers with corn pollen to the rivers, canyons, and the sky. There are cultural sites and different types of animal species that inhabit the land. The Confluence area is sacred to military veterans. It is where prayers were offered when Navajo military people were leaving for war back in the 1960s. Traditional ceremonies were performed down by the Colorado River and above the canyon for the safe return of our Navajo soldiers who fought for our country.”

The need for tribal consultation

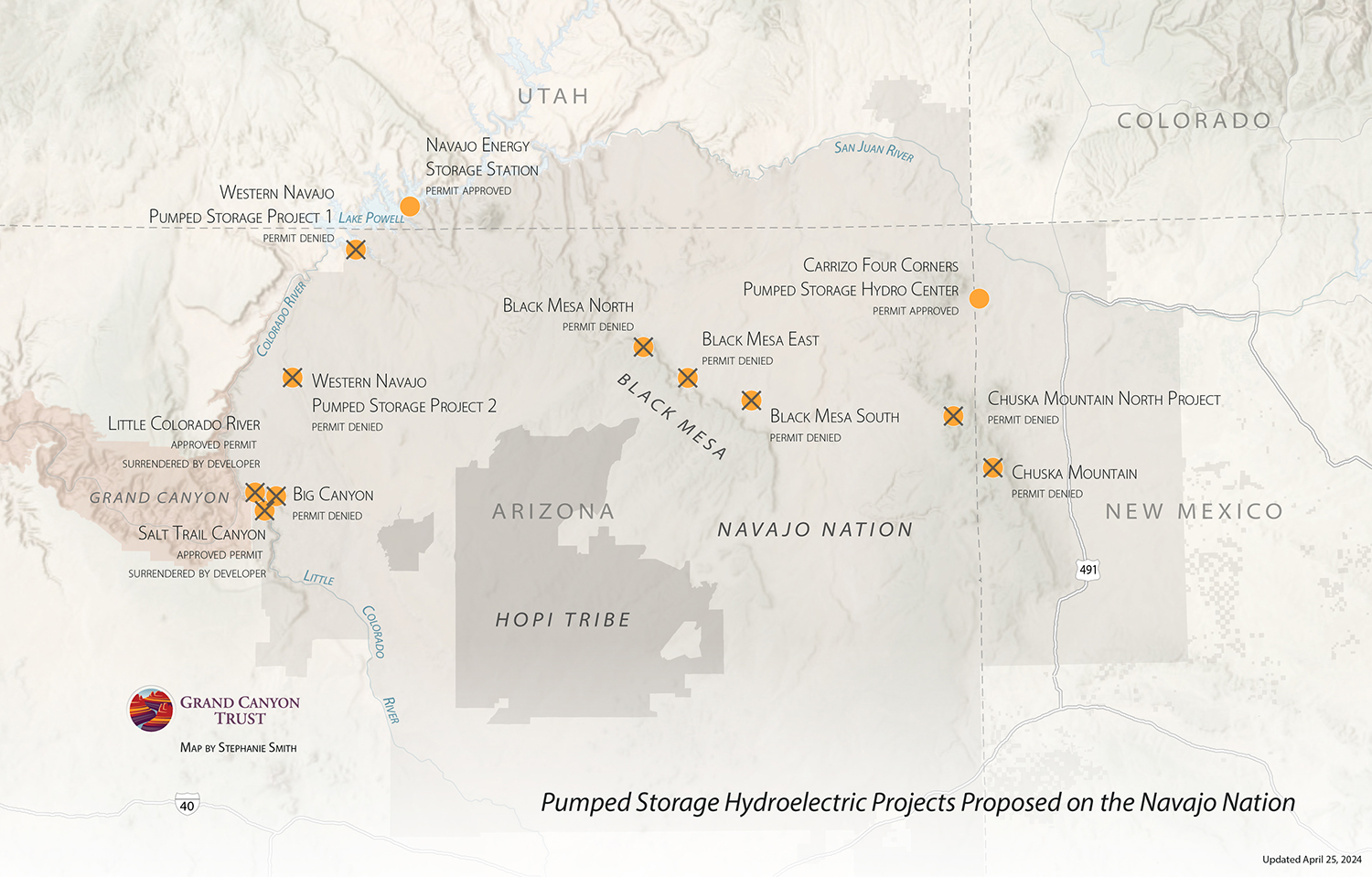

The commission’s decision to deny the Big Canyon Dam permit comes on the heels of decisions striking down seven other hydropower dam proposals on Navajo Nation land that the Navajo Nation had opposed. While the new commission policy requiring a tribe’s consent for preliminary permits to be issued for hydropower projects on the tribe’s land is good news for tribal sovereignty, it doesn’t address the need for tribal consultation.

Many tribes maintain strong cultural ties to lands that are outside their current reservation boundaries and want to be consulted before projects are permitted on their ancestral lands.

As an example, the U.S. Department of the Interior’s 2020 comments on the Big Canyon project noted that the project would affect tribes with cultural connections to the area, including the Navajo Nation, the Havasupai Tribe, the Hopi Tribe, the Hualapai Tribe, the Kaibab Band of Paiute Indians, the Las Vegas Tribe of Paiute Indians, the Moapa Band of Paiute Indians, the Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah, the San Juan Southern Paiute Tribe, the Yavapai-Apache Nation, and the Pueblo of Zuni.

Earlier this year, the Hopi Tribal Council passed a resolution to ask the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to change its rules regarding tribal consultation and consent for pumped storage hydroelectric projects on tribal lands and ensure that tribes have a seat at the table when it comes to decisions about projects on their ancestral lands.

The Big Canyon decision is a victory for the Navajo Nation, the Hopi Tribe, the Hualapai Tribe, grassroots groups like Save the Confluence, and many others who have worked tirelessly to defeat this project and protect the Little Colorado River and Grand Canyon region for future generations. It’s also a victory for the river and the Grand Canyon itself, and for its waters, plants, and creatures.