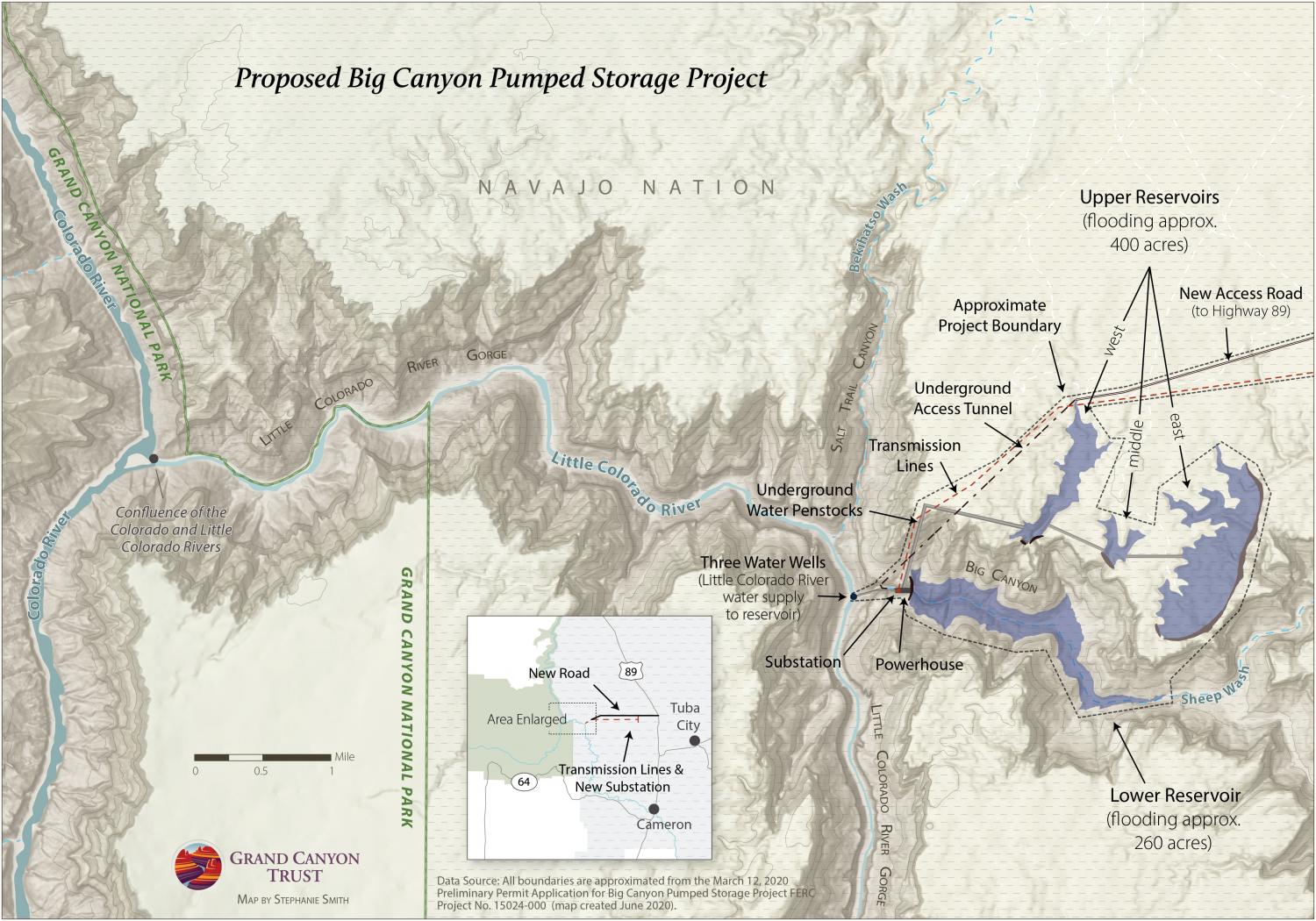

For the third time in less than a year, developers have proposed to dam tributary canyons to the Colorado River on the Navajo Nation near the Grand Canyon. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) has closed the 60-day period to comment on the Big Canyon hydroelectric project after being flooded with missives from the public, local communities, and tribal nations. The proposed dams would irreparably harm the Little Colorado River.

The Grand Canyon Trust submitted over 62,000 comments from the public and, represented by Earthjustice, filed a motion to intervene to oppose the project along with a coalition of conservation groups.

The Navajo Nation, affected sheep and cattle ranchers, and tribal nations with strong cultural and religious ties to the area filed formal notices opposing the Big Canyon project. And they strongly criticized the dam developers’ and FERC’s failure to consult the people on whose land the latest dam proposal would be built. Indigenous communities with ancient ties to the area also objected strenuously to the disrespect displayed for tribal sovereignty.

Developers didn’t seek the consent of the Navajo people

In opposing the project, which would be located entirely on Navajo Nation land, the Navajo Nation said the developer “has not sought the consent of the Navajo Nation, the local community (Bodaway-Gap Chapter), or the individuals with customary use rights where the Project would be located.” It also pointed out that “the Nation has not authorized the permit holder to enter upon the lands of the Navajo Nation or to use its waters.”

Unphased, a representative for the Phoenix-based dam developer, Pumped Hydro Storage LLC, told the Guardian, “Where this is located, hardly anybody will see it. It’ll be in a hole.”

Paul Begay, the Navajo Nation council delegate who represents the Bodaway-Gap Chapter of the Navajo Nation, sees the developer’s “hole in the ground” differently. The area is sacred and, Begay explained, “the land is our church.”

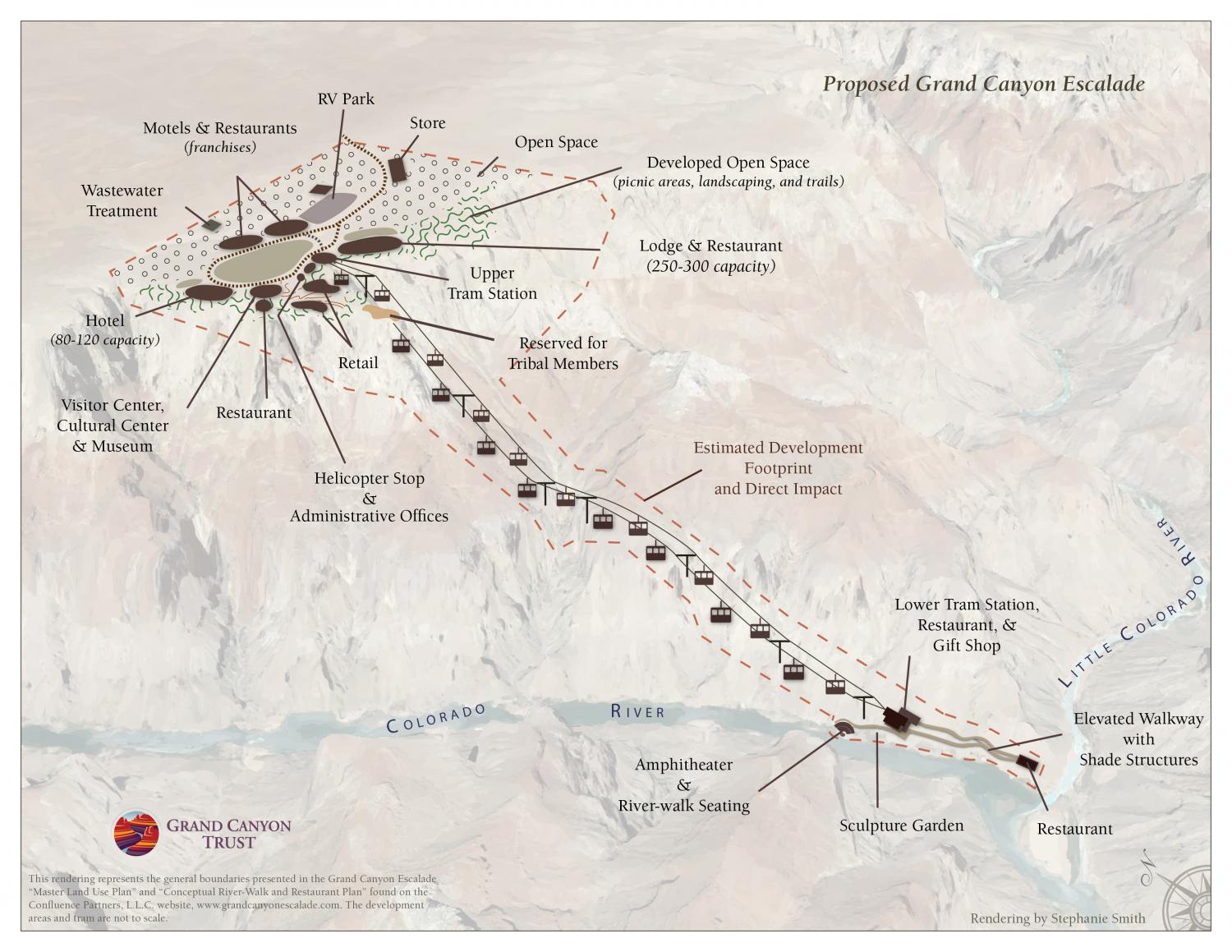

Rita Bilagody, a local resident and member of the Navajo grassroots organization Save the Confluence, was outraged to have to again defend this sacred land where another developer previously tried to build a tram from the rim to the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado rivers. “This is another outside developer who professes to do all these things for us,” she said. “But it doesn’t benefit us, it’s for them.”

Long-time resident and Save the Confluence member Willie Longreed added that the developers are all about money. “We don’t worship like they do.”

Save the Confluence was instrumental in defeating a proposed tourist resort and tram near the same area in 2017.

To oppose the developer’s application to dam Big Canyon, the grassroots coalition worked safely during the pandemic to secure signatures of opposition from local ranchers who hold permits to graze in the area, obtaining a resolution opposing the project from the local grazing district. This matters because under Navajo law a development cannot move ahead without the unanimous consent of local grazing-permit holders.

FERC process disrespects sovereign nations

The Navajo Nation has requested “meaningful government-to-government consultation with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission before any formal action is taken pursuant to the disposition of the application.”

Former Navajo Nation legislator and Save the Confluence adviser Larry Foster objected to FERC’s disrespectful process of accepting applications and issuing permits without first consulting with the Navajo Nation. “They need to know we have a treaty,” he said. “Basically, the Navajo Nation is looking to reinstate its sovereignty.”

The Hopi Tribe also filed a motion to intervene against the project, calling the proposed location of the dams “simply unacceptable to Hopi religious leaders, practitioners and the Hopi people as it will significantly and forever adversely impact sacred places.”

The Hopi Tribe pointed out that the Navajo Nation could deny the dam developers access to the land to conduct feasibility studies, a fact FERC had itself acknowledged could make it difficult for the developer to actually prepare an adequate application to dam Big Canyon.

The tribe also noted that FERC had dismissed tribal concerns as “premature” when previously issuing preliminary permits to the same developers for two prior projects to study damming the Little Colorado River, but underlined that it was wrong to dismiss as “’premature’ comments relevant to the project location on Native American land.”

The Hopi Tribe also reiterated that government-to-government consultations between the Hopi Tribe and the U.S. federal government are required before FERC can consider the private developers’ preliminary application to build dams on sovereign land.

The Hualapai Tribe’s comments took aim at the dam developer’s statement to the Arizona Republic that “I’m just concerned with Navajo. It’s Navajo ground. It’s not Hualapai ground and it’s not Hopi ground,” saying that it “demonstrates an ignorance of law and policies that require meaningful consultation with all tribes that may be affected.”

The Hualapai comments further asserted “…the fact that FERC is considering this application without involvement or consent from the Navajo Nation, without prior consultation, is an affront to tribal sovereignty.”

FERC took about six months after the comment period closed to decide to issue preliminary permits on Pumped Hydro Storage’s two previous applications to dam the Little Colorado River. If it repeats that pattern, it could render a decision in early 2021.

Perhaps, this time around, more strongly worded comments will cause FERC to deny the Big Canyon application because tribal nations clearly don’t want it.

However, this federal commission has a record of rubber-stamping controversial energy projects and pipelines.

Veteran activists look ahead

Rita Bilagody said that it all boils down to “The arrogance of the white man. They feel like they can do anything and everything that they’d like to do.” Larry Foster added “It’s part of the systemic racism that still exists.”

“We still live here,” Bilagody added, “and we’re going to fight this.”