Over 200 bird species call the Grand Staircase-Escalante region home.

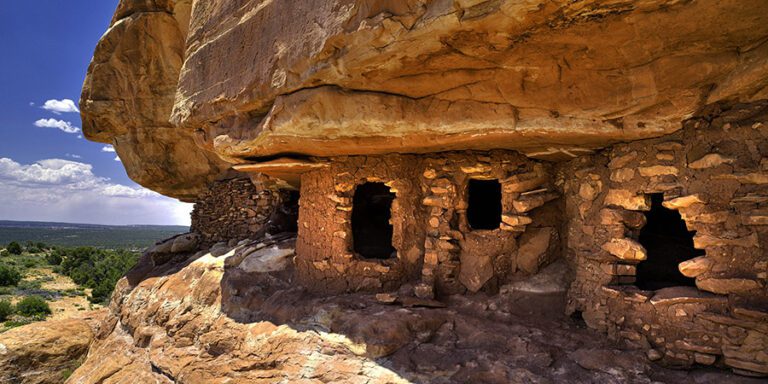

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument is 1.9 million acres of towering cliffs, slickrock, and sweeping plateaus in southern Utah. Abundant archaeological sites in this cultural landscape demonstrate the long history of Indigenous peoples who still maintain strong cultural ties to the area.

The landscape holds a library of fossil records, including a complete skeleton of a Poposaurus — a rare bipedal crocodile-like creature. And the monument’s wide range of habitats support a plethora of modern-day animals too.

Whether tucked into lush creekside vegetation, soaring high above rocky cliffs, or flitting through old-growth forests, over 200 bird species call the Grand Staircase-Escalante region home. Here are a few of our favorites:

Southwestern willow flycatcher

As its name suggests, the Southwestern willow flycatcher is an insectivore, nimbly snatching bugs — from flying ants to gnats to dragonflies — out of the air. But this sprightly, slender bird is federally endangered. Diversions, dams, and groundwater pumping have dried up the water sources flycatchers rely on. Streamside cottonwood and willow trees have withered. Cattle have eaten and trampled native plants. And the steady creep of invasive tamarisk shrubs have led to a significant loss of lush wetlands — the flycatcher’s desired habitat.

Keep your eyes peeled near the reliable waters of the Paria and Escalante rivers, which make these vibrant, green oases a good home for the small olive-and-gray-colored flycatcher. Approximately 1,300 pairs of flycatchers breed in the southwestern United States between May and September each year.

California condor

The bald-headed California condor is North America’s largest bird and an iconic story of recovery. An efficient scavenger, condor populations declined, the birds poisoned by lead after feeding on ammunition-filled wildlife carcasses. Back in the 1980s, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service placed the remaining handful of endangered California condors in a captive breeding program. Now, captive-bred condors released in the wild fly free with wild-born condors. Around 100 patrol the skies of northern Arizona and southern Utah.

The unmistakable black condor has a wingspan of 9.5 feet and weighs up to 25 pounds. It boasts a pink and orange bald head and a brilliant white lining under its wings. Spot condors on the western side of Grand Staircase, nesting on steep cliffs near Zion National Park. Or visit the Vermilion Cliffs to watch captive-bred condors released into the wild each September.

Mexican spotted owl

Mexican spotted owls can be found in the canyonlands and old-growth pine forests of the desert Southwest, at home roosting or nesting among large trees, small sources of water, and dense cover. The aptly named owl is medium-sized, chestnut brown with white spots all over. It has dark eyes and does not have tufted ears.

Historically ranging across the Four Corners region, Mexican spotted owls are now threatened due to forest management practices that remove old-growth forests and increasingly destructive wildfires across the region.

When out camping in the canyons of Grand Staircase-Escalante, listen for their calls echoing through the night, a series of deep sounds in a “hoot, hoot-hoot, hoot” pattern.

Not every bird in Grand Staircase-Escalante is threatened or endangered, but alarm bells are ringing for some declining species, like the pinyon jay.

Pinyon jay

The sleek, blue-gray pinyon jay nests, forages, and caches food in pinyon pine and juniper forests across much of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. A single pinyon jay can store up to 20,000 pinyon seeds in a season! It remembers where it hid them 95 percent of the time, which means the seeds left behind can grow the next generation of trees.

But pinyon jay populations have nose-dived, declining 85 percent since the 1970s as their habitat disappears, sometimes leveled to make room for cattle.

Hardy pinyon pine and juniper trees can withstand harsh winters and hot, dry summers, often living upward of 500 years, but they’re no match for federal agencies clearcutting ancient pinyon and juniper forests. You can help by birdwatching in the name of conservation — look (and listen) for noisy groups of pinyon jays moving through the trees and document your observations.

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument may be known for its geology and paleontology but take a look around and you’ll see that the landscape is teeming with a diversity of living creatures. These amazing avians are just a few of the wonders that you may catch sight of during a visit.