To do so, it sets state-specific goals for “carbon intensity”—the average amount of carbon dioxide emitted for each megawatt of electricity generated. However, it lets states choose how to best meet that goal. It affords flexibility to choose from a menu of policy “building blocks” to meet state-specific reduction goals by:

The Plan also gives states the option to create a trading program to cap carbon emissions (“cap and trade”). It lets them develop individual or multi-state plans to meet goals. If a state doesn’t come up with an effective plan of its own, the EPA will make one for them. Importantly for the Colorado Plateau, power plants in Indian Country–four in our region, including Navajo Generating Station and Four Corners Power Plant–are exempted from the rule. EPA will work with tribes and sources to develop or adopt Clean Air Act programs.

Most of the electricity generated on the Colorado Plateau comes from burning fossil fuels. As of 2010, there were 51 fossil fuel powered plants on or within 50 miles of the Colorado Plateau. They generate about 132 million-megawatt hours and about 23,700 megawatts of electricity by burning coal, natural gas, or oil.

Table 1 provides a break down those plants’ electricity generation, carbon intensity and carbon emissions by plant fuel type. Note that the table does not display total energy production on the Colorado Plateau—because renewable and hydro energy make up a very small percentage of generation regionally.

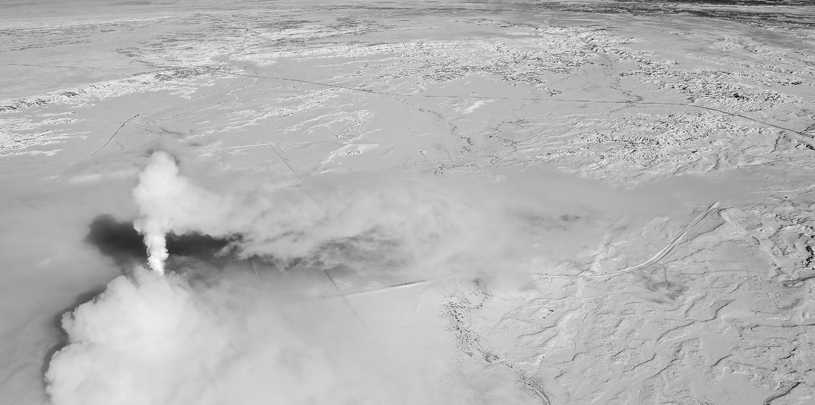

When it comes to megawatts generated on the Colorado Plateau, coal is king. Most electricity produced in our region comes from coal-fired power plants—over 75% of the megawatts and 86% of the megawatt hours, according to 2010 data. The map below depicts that fact—where dot size shows generating capacity, and color depicts fuel source.

Coal burning creates the vast majority of power plant carbon emissions on the Colorado Plateau too: the biggest carbon emitting fossil fuel plants burn coal, and 94% of all fossil fuel plants’ carbon dioxide emissions come from coal plants. The map below illustrates this, showing carbon emissions for power plants according to their fuel type.

But coal plants don’t just emit more carbon because they produce more electricity; they’re also less efficient—and thus more carbon intensive—than other power plants. They emit more carbon per megawatt than other fossil plants. Recall that that carbon intensity is a primary metric for the Clean Power Plan’s state goals; the following map shows the carbon intensity of Colorado Plateau power plants.

Though coal makes up the lion’s share of the Colorado Plateau’s carbon pollution problem, another important part of the picture—at least as it pertains to the Clean Power Plan—is the dearth of non-hydro renewable energy generation. Despite abundant solar and wind resources in Arizona and Utah, both states lag behind much of the nation in clean, renewable energy generation. In fact, they cannot even keep up with their neighboring states.

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

The Clean Power Plan proposes substantial reductions in carbon emissions from Colorado Plateau power plants. Table 2 shows 2005 emission rates (in carbon intensity—carbon emissions per megawatt) and the Clean Power Plan’s targets for 2030 for five states in the region.

Those goals correspond to state-by-state emission reductions shown below in Chart 1. Chart 1 also shows how EPA suggests those emissions rates can be achieved, by category (but remember, how those reductions are actually achieved is up to the states).

Chart 1: The Clean Power Plan proposes to reduce CO2 emissions from existing power plants by between 27 and 52% from 2005 levels in states on or near the Colorado Plateau.

Coal is the Colorado Plateau’s carbon problem. While in theory states can choose among a variety of measures to meet emissions reduction goals, in reality, our region’s heavy reliance on coal makes reducing those plants’ emissions an inevitability of the Clean Power Plan. In short, state goals won’t be met without reducing coal plant emissions.

For that, EPA’s plan identifies two options: States can require greater heat rate efficiency of generating units (blue in Chart 1), or they can reduce emissions from the most carbon-intensive plants by substituting generation from those units “with generation from less carbon-intensive affected units (including natural gas combined cycle units that are under construction)” (red in Chart 1.). But technology to increase power plant heat rate efficiency is limited and expensive; it’s a more limited option than turning to natural gas.

Thus, under the Clean Power Plan, coal’s future on the Colorado Plateau becomes even more tenuous. It comes as efficiency, solar and other forms of electricity become increasingly cost-competitive with coal, and as coal plant owners already face increasing costs to upgrade old, polluting plants.

EPA’s suggested reliance on new renewable energy–or, its lack of reliance on renewable energy–is also of interest. Despite its abundant solar resources, for example, the agency suggests that by 2030 Arizona increase its renewable energy generation to only 4% of all power generation. In contrast, Colorado and New Mexico are pegged at 21%. Economic and environmental benefits would attend a more aggressive approach to renewable energy generation across the board–and especially in Arizona and Utah.

With major cutbacks in coal, but marginal gains in renewable, something has to fill the generation gap. For that, EPA suggests natural gas. For anyone who follows gas development on the Colorado Plateau, you know that prospect is complicated.

Part two of our Clean Power Plan blog installation will discuss that and other complications of the plan–including Indian Country’s exemption and some of the expected winners, losers, and legal battles.

In the meantime, you can learn more about the Clean Power Plan by visiting EPA’s website here. For policy wonks, we recommend a series of articles by our friends at Legal Planet here.

Leave A Comment