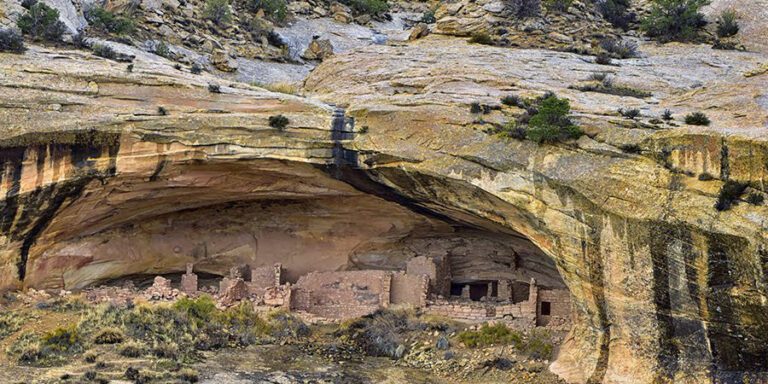

As abandoned uranium mine waste is cleaned up inside Bears Ears National Monument, new mining claims prepare to dig in.

As the Bureau of Land Management makes plans to mitigate a large pile of abandoned toxic and radioactive mine waste inside the original Bears Ears National Monument, Utah’s Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program is doing award-winning work cleaning up lands in and around the original monument. So far, the program has sealed dozens of abandoned mine shafts and removed toxic materials in the Fry Canyon and Red Canyon uranium districts. Now, it’s turning to work on the White Canyon and Deer Flat uranium districts (both within the Bears Ears’ original boundaries) to enhance public safety. It’s part of a 400-square-mile project to begin to heal the land from a Cold War uranium boom that took place in the Bears Ears region from 1947 to 1970, when the U.S. government was heavily subsidizing uranium mining to build its nuclear weapons stockpile.

New uranium mine planned in Bears Ears

Though most active uranium mining in the region ended when government subsidies ended, former President Trump’s unlawful reduction of Bears Ears in 2017 opened a door to new uranium mining. In spring 2021, a plan of operations was filed for a new uranium mine in the original Bears Ears National Monument on Deer Flat. This is exactly the area that is the subject of ongoing cleanup.

The plan for the new mine calls for digging out a mine portal, constructing vent shafts, disturbing ground for a man camp, and widening roads before gating at least one of them to lock out the public on Deer Flat above Natural Bridges National Monument and inside the original Bears Ears. That’s exactly the disturbance that the multiyear, multimillion-dollar Abandoned Mine Reclamation Program is trying to reverse.

We know that uranium was a key driver behind Trump’s unlawful 2017 reduction of Bears Ears National Monument, and when the former president slashed the boundaries by 85 percent, the bulk of the region’s uranium deposits were cut from the monument.

Mining public lands, paying zero royalties into public coffers

Hardrock mineral extraction (including uranium) is governed by the General Mining Act of 1872. This is an antiquated law meant to encourage colonization and westward expansion. It allows anyone to stake a mining claim on federal lands. Then, if the claimant proves a profit can be made, to mine publicly owned minerals without paying royalties.

This differs from oil and gas leasing (also in the news in June when industry nominated more than 40,000 acres of lands cut from Bears Ears) which requires royalty payment, agency review, and public involvement before leases are let and before drilling can begin. The Bureau of Land Management can simply say “no” when asked to offer a parcel for an oil and gas lease, but the 1872 mining law has no such provision. According to Earthworks, “[f]ederal land managers are on record declaring that the 1872 Mining Law gives them no choice but to permit mining… If you hold a mining claim, the federal government treats that claim as a right-to-mine.”

Uranium mining and new mining claims in Bears Ears

When national monuments are designated, no new mining claims can be staked on national monument lands. When former President Trump gutted Bears Ears, he also allowed for mining claims and oil and gas leasing on lands he cut from the monument. That has led to the filing of new uranium and vanadium claims at Bears Ears — at least 14 since the monument was slashed, six of them just since March 2021.

One such claim led to the excavation of the Easy Peasy Mine in 2018. There, 30 tons of ore were excavated, and now, due to low uranium prices, the mine sits idle. The miner at Easy Peasy is the same one who recently filed the plan of operations for the new mine on Deer Flat, and he told the Washington Post in April 2021 that “a restored Bears Ears monument would make Easy Peasy hard — if not impossible. ‘There is layer after layer after layer of red tape and regulation in this country,’ [the miner] said. ‘And that monument will be one more big blanket of red tape.’”

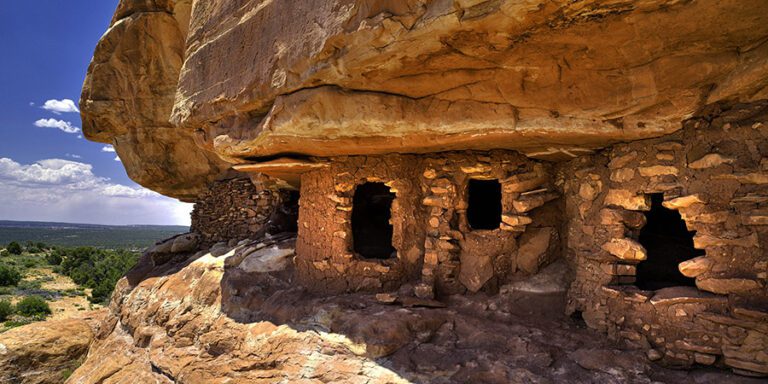

An Indigenous take on uranium — leave it alone

When Bears Ears National Monument was designated in 2016, it became the first national monument in America to honor Indigenous traditional knowledge. “Such knowledge is, itself, a resource to be protected and used in understanding and managing this landscape sustainably for generations to come,” reads President Obama’s proclamation.

While there are many knowledge systems at play at Bears Ears, one stands out for its specific understanding of uranium. Diné (Navajo) people know uranium as “leetso” (literally translated as “yellow brown” or “yellow dirt”), but it’s more than that. Leetso is a being that interferes with one’s ability to enjoy a successful life. Leetso is also a reptile, a monster, buried and not to be disturbed.

The uranium boom on the Colorado Plateau from the 1940s to the 1970s disturbed leetso, and the consequences continue in the form of cancers among those who mined uranium, and elevated health risks for those whose land, air, and water still bear contamination from unearthing and spreading this monster. In response, the Navajo Nation banned uranium mining and processing within their borders in 2005, and the nation supports the restoration and expansion of Bears Ears National Monument, in part to keep the uranium found there buried. In Diné cosmology, monsters can be slayed with a plan and action. Doing so restores hózhó, or balance. The plan and action here should be to bury leetso again, forever, by restoring and expanding Bears Ears National Monument.