by Tim Peterson, Utah Wildlands Director

by Tim Peterson, Utah Wildlands Director

The 2016 proclamation establishing Bears Ears National Monument protected a living cultural landscape. Despite more than a century of archaeological study, much of how ancient peoples lived at Bears Ears remains shrouded in mystery.

The current administration’s 2017 assault on Bears Ears cut the monument by 85 percent, and in doing so, removed the focus on the proper care and management of important cultural resources found within the original boundaries. In addition to cutting out what may be the oldest known sample of rock art in North America, a particular set of features — Chaco — lost big in the decimation of the boundaries.

No, not your Chaco sandals. The Chaco Culture, as archaeologists call it, was a particularly vibrant and prominent cultural influencer centered on Chaco Canyon, New Mexico at around A.D. 1000. Chaco Canyon itself is home to some of the most elaborate ceremonial structures built by Ancestral Puebloans.

Flourishing from the ninth to the 13th century, the profound influence of the Chaco Culture spread across the present-day boundaries of the Four Corners region. The northwestern-most Chacoan outposts are found in and around the original boundaries of Bears Ears National Monument. These features include great houses (community gathering spaces), great kivas (religious structures), and great roads.

The great roads aren’t roads simply in the way we think of them today — a way to get from point A to point B quickly and efficiently — they are much more than that. They often extend perfectly straight for many miles, running up and down cliffs, across ravines, and through deep canyons. Utah’s great roads vary slightly from the core Chaco Canyon standard, curving gently here and there along canyon rims as terrain dictates. Chaco Canyon’s broad, open plains made perfectly straight roads more readily achievable.

In Bears Ears, these roads may predate the zenith of the Chacoan period by two centuries, as evidence shows they were formalized and built by around A.D. 800. Some may even be as old as 500 B.C. and may have been built on top of earlier roads used since the Basketmaker period. Since the Bears Ears roads are older, they may in fact have influenced the Chacoan societies, not the other way around.

Since they weren’t designed exclusively for transportation or trade, these roads are thought to hold spiritual and metaphysical value. Ancestral Puebloan oral history reasons that the roads draw the spiritual significance of the surrounding cultural landscapes into the great house and great kiva sites, and allow the spirits of newborns to arrive and the departed to travel to another plane. The great roads may connect distant great houses and great kivas, or they may unite with significant regional landforms. For example, one road in Utah may connect the great house at Bluff with the Bears Ears buttes themselves.

The great roads were massive public works projects that required enormous investment of labor from a society that did not have the wheel or beasts of burden to assist with construction. The great roads include waypoint markers or shrines — called herraduras by archaeologists — along their course, often where they change direction. Many were built near or through earlier settlements, perhaps as a way to honor ancestors.

Bears Ears is also replete with mesa-top signaling stations that were used to communicate between farming and living areas. These are indicators of a sophisticated and highly organized society. Today, no one lives permanently on the public lands of Bears Ears; a thousand years ago, the region was bustling with a network of population centers and connected farming and hunting grounds. Thousands of significant sites have not been documented, studied, or excavated, and perhaps they never will be. Pueblo people today want these sites, particularly burial sites, left undisturbed so that their ancestors may rest peacefully.

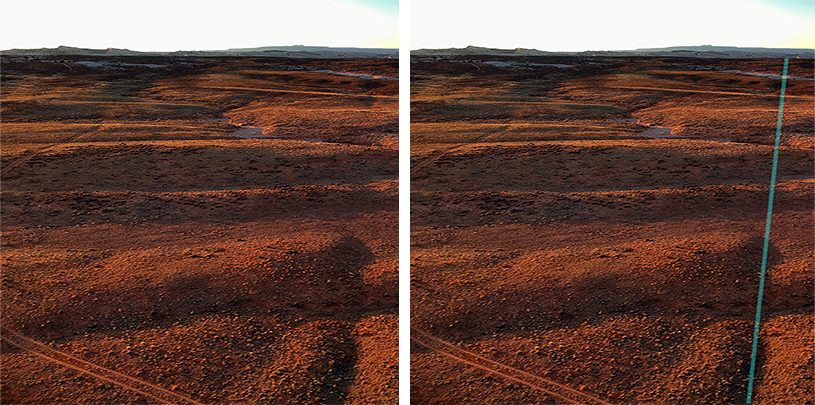

Study and modern identification of Utah’s great roads is still in the early stages. The roads can be difficult to discern and can only be properly photographed with low-angle light — just after sunrise and just before sunset. Archaeologists have documented about a dozen road segments in the Bears Ears region.

Scientists are also just beginning to record fascinatingly precise solar, lunar, and constellational alignments present within the construction of Chacoan structures, giving rise to a relatively new field of scientific study known as archaeoastronomy. Previously unknown to researchers, modern scientific means of measurement are finally catching up with what the Ancestral Puebloans knew and implemented in their construction more than a thousand years ago — all without GPS satellites and computers. These things yet to be rediscovered are exactly why national monument designation is so important — to ensure protection, promote contemplation, and allow stories of our shared human history to be told.

The December 2017 proclamation shrinking Bears Ears claims that the cultural resources cut from the monument are “not unique” and “not of significant scientific or historic interest.” Highlighting the slapdash nature of Secretary of the Interior Zinke’s national monuments review, President Trump’s proclamation removed national monument protection from at least two dozen highly significant Chacoan sites — the majority of the Chacoan outlier sites in the region. Those living near Bears Ears a millennium ago put their personal stamp on the Chaco building model; variations and anomalies in these sites make them different from those in New Mexico, Arizona, and Colorado. Sites like these are found nowhere else on Earth. Calling them “not unique” and “not …of interest” is not accurate.

These Chacoan sites are a very small sample of the tens of thousands of significant, unique, irreplaceable, and fragile cultural sites left vulnerable by President Trump’s shrinkage. These sites, which preserve a 13,000-year span of human history, now face real threats from oil and gas drilling, uranium mining, and gravel-pit expansion. That’s a grave injustice. The original Bears Ears National Monument must be restored and expanded. We owe it to our past; we owe it to our future.

80% of Arizona voters support Baaj Nwaavjo I'tah Kukveni National Monument, according to a new poll.

Read MoreUtah voters strongly support national monuments in general, and Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante in particular, a new poll shows.

Read MoreA small victory in the legal case challenging Daneros uranium mine, near Bears Ears National Monument.

Read More