Two down, one to go.

On July 26, 2021, the would-be Little Colorado River dam developer asked to surrender two preliminary permits for proposed hydroelectric dam projects on Navajo Nation land near the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado rivers in the Grand Canyon. The developer asked to cancel the permits for the proposed Little Colorado River and Salt Trail Canyon dams after being notified by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) that it was already out of compliance with permit requirements.

There’s no question here: We’re counting this as a big win. Since 2019, the Navajo Nation, Hopi Tribe, Hualapai Tribe, the families of the Navajo grassroots organization Save the Confluence, and others have worked to oppose these unwanted proposals by Phoenix-based developer, Pumped Hydro Storage LLC. In its requests, the company cited strong opposition from the Navajo Nation, environmentalists, and others, as well as high costs as the rationale for surrendering the permits. No one can deny that this victory belongs to many strong advocates across the country. The decision to surrender the permits for these two projects is a testament to the hard work of tribes, community organizers, and concerned citizens like you who took action and submitted comments.

ADAM HAYDOCK

ADAM HAYDOCK

These dam proposals surfaced just two years after the defeat of the Escalade tram proposal at the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado rivers that left community members drained and looking for a path to healing. Save the Confluence members who worked tirelessly to defeat the tram proposal were hoping to pivot from being reactionary to planning for long-term safeguards for the lower Little Colorado River. Instead, they learned that threats to the confluence had changed from trams to dams. The 2019 Little Colorado River and Salt Trail Canyon dam proposals, followed by the proposal to dam Big Canyon in 2020, all fall on Navajo Nation land in a natural landscape of deep cultural importance to many Grand Canyon-affiliated tribes. FERC awarded the first two preliminary permits in 2020 despite interventions and objections from the Navajo Nation, the Hopi Tribe, the Hualapai Tribe, and conservation organizations including the Grand Canyon Trust.

It was problematic that the developer was able to obtain permits without getting consent from the Navajo Nation, underscoring deep flaws in the FERC permitting process. Had these two dam proposals advanced, it would have been a direct affront to tribal sovereignty and the right to free, prior, and informed consent as recognized by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Unfortunately, the developer’s requests to surrender these two permits are a reminder that we have only cleared some of the hurdles. The Big Canyon dam remains the developer’s priority — and our biggest concern.

STEPHANIE SMITH

STEPHANIE SMITH

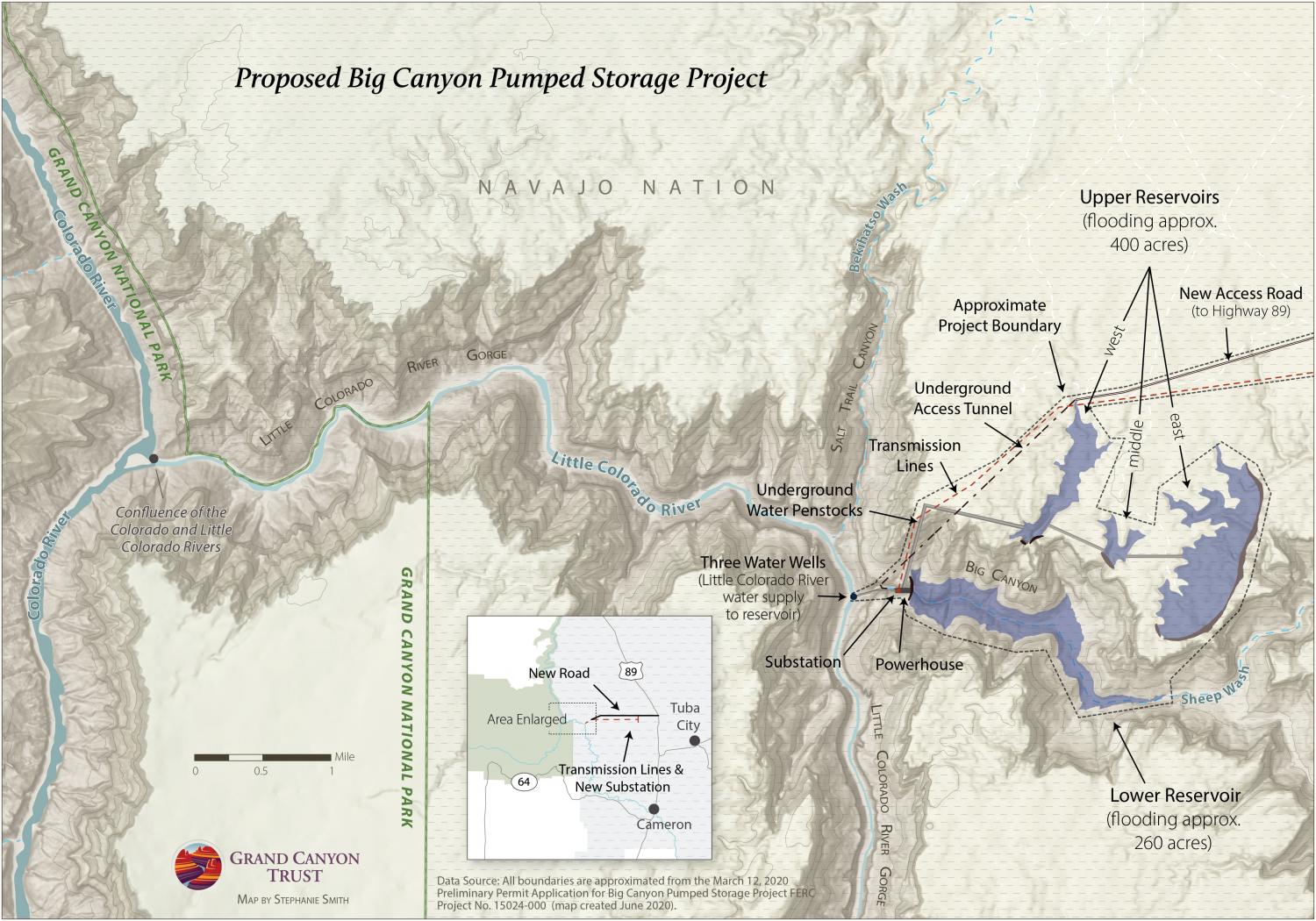

Upstream of the other two proposals, the Big Canyon project would require four storage reservoirs in and above a tributary canyon to the Little Colorado River Gorge. The impacts would be severe. Filling the reservoirs associated with the dam would require pumping billions of gallons of precious groundwater from the aquifer. The depletion of this aquifer could alter Blue Spring, which feeds the turquoise waters of the Little Colorado River. The lower Little Colorado River flows perennially into the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon, and its warm waters shelter the endangered humpback chub.

The developer is proposing to pump 14 billion gallons of groundwater to fill the four Big Canyon reservoirs, plus an additional 3.2 to 4.8 billion gallons per year to make up for evaporation loss. These numbers are alarming in a desert landscape, especially considering the current potable water restrictions in place across the Navajo Nation. Nonetheless, the developer is continuing to push a proposal to pump additional groundwater in order to produce electricity for distant city centers in the middle of this megadrought.

It is unknown when FERC will decide on the Big Canyon preliminary permit application that the developer submitted in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. If granted, the permit will initiate a 3-year period for a feasibility study. As of now, the Navajo Nation has indicated that the developer is not welcome on Navajo Nation land. After the Escalade tramway proposal and the 43-year development ban in the region known as the Bennett Freeze, the continued extraction of Native resources to benefit outside corporations is a far cry from the culturally appropriate economic solutions sought by local communities and tribal governments.

JACK DYKINGA

JACK DYKINGA

The Trust will continue to stand in support of tribes and communities opposing this unwanted proposal. There are solutions we can support at the tribal level, like a Navajo Nation sacred site designation and just transition work. But without a doubt, we will need to turn our attention to supporting policy and legislative solutions, at the direction of tribes, that prevent commercial developers from proposing dams on Indigenous waterways without tribal consent.

The lower Little Colorado River and confluence are spiritual places best left untouched by development, as grassroots community members and tribes have requested. Upstream dams could alter this place of reverence and beauty. After years of fending off the Escalade proposal, this landscape needs a reprieve for healing. By supporting local communities, we intend to give it that.

Amanda Podmore directs the Grand Canyon Trust’s Grand Canyon Program.

Amanda Podmore directs the Grand Canyon Trust’s Grand Canyon Program.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The views expressed by Advocate contributors are solely their own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Grand Canyon Trust.