BY SARANA RIGGS

For most of its length as it winds through the Painted Desert, the Little Colorado River is a dry, cracked riverbed where only flash floods and spring snowmelt send torrents of muddy water raging downstream. But high in Arizona’s White Mountains, its headwaters run clear and cool. And deep in the heart of the Grand Canyon, near its confluence with the Colorado River, spring-fed year-round flows take on a beautiful milky-blue hue and turn rich brown with silty runoff after storms.

It is here, in this pristine, remote stretch of the Little Colorado River Gorge on the Navajo Nation, near Grand Canyon National Park, that developers aim to back up ancient waters behind concrete dams.

The Little Colorado River is known by many names to the 11 tribes affiliated with the Grand Canyon. As a Diné (Navajo) woman from Western Navajo Agency, I call the Little Colorado River Toh Bi Kaah, meaning “water above.” Since time immemorial, the Little Colorado River’s precious waters have meant life to Indigenous peoples in the Southwest. While hard to reach, it’s been home since we emerged from the canyon’s depths. This river has many connections to many tribes from its headwaters to all the tributaries that flow into this place where we say prayers, collect medicines, and make pilgrimages to our most sacred spaces.

In such an arid landscape, the Little Colorado River is also a safe haven for plants and animals. Blue Spring feeds the lower-most 13 miles of the river — its perennial turquoise waters a refuge for the federally endangered humpback chub and seven species on the Navajo Endangered Species List. Birds, plants, and wildlife abound.

ADAM HAYDOCK

ADAM HAYDOCK

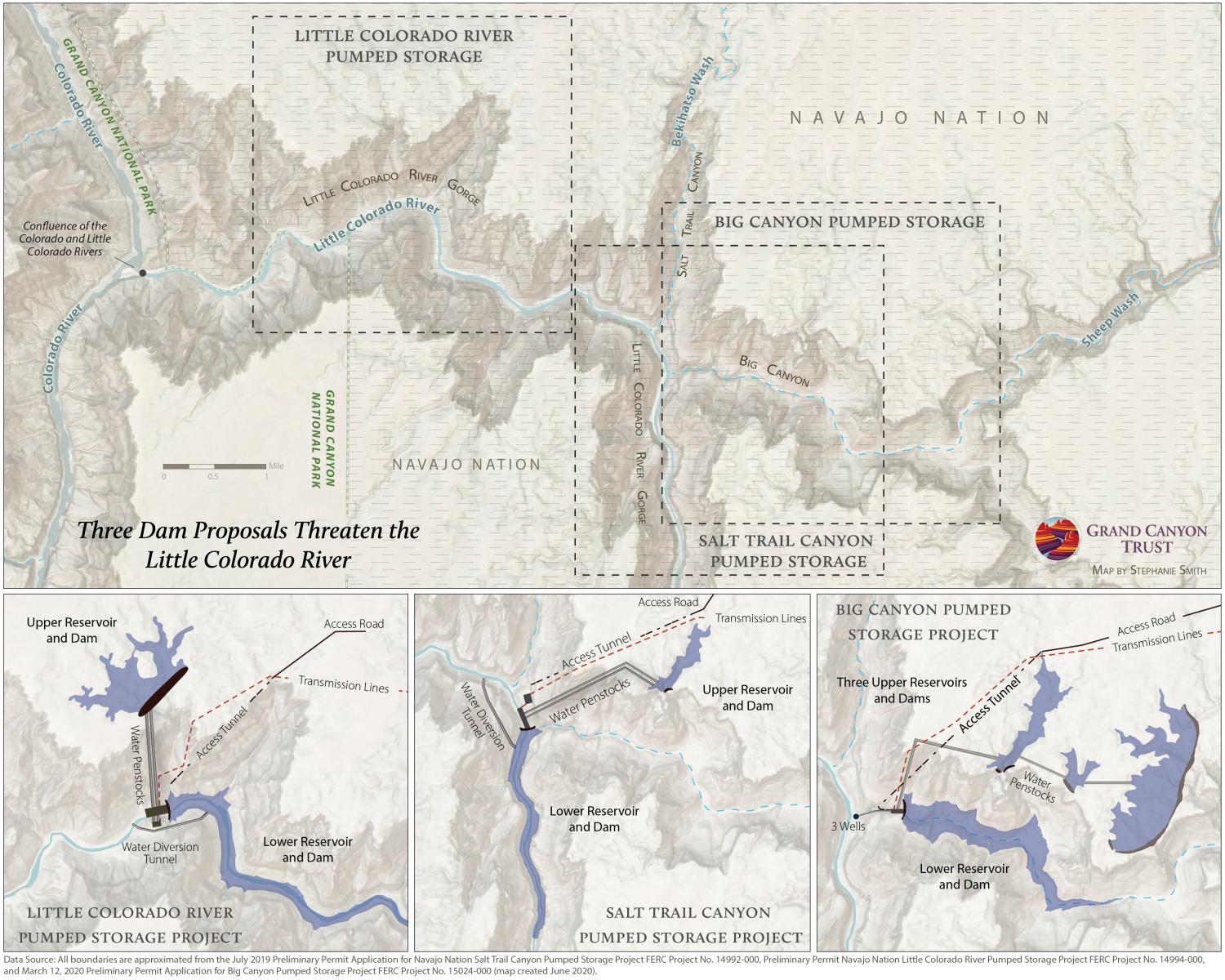

Now, that natural and spiritual life-source is at risk. A Phoenix company called Pumped Hydro Storage LLC is pursuing three hydroelectric projects on and above the Little Colorado River and its tributaries. Each project varies slightly in location and design, but all would desecrate and destroy cultural sites and fragile habitats, and forever alter the river that has sustained Native people for millennia.

The projects, called “pumped storage projects,” generate electricity by moving water between reservoirs at different elevations. When energy demand is low, water is pumped uphill into the upper reservoirs, where it’s held until people start switching on lights, televisions, and air-conditioning units. At peak demand, water can be released to the lower reservoirs, falling through turbines to create electricity.

In May 2020, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) issued preliminary permits for two of the projects despite objections from the Navajo Nation, the Hopi and Havasupai tribes, the Arizona Game and Fish Department, and a host of conservation organizations including the Grand Canyon Trust.

The Little Colorado River Pumped Storage Project would back up approximately three miles of the namesake river behind a 150-foot-high dam about a half mile from Grand Canyon National Park and flood important cultural areas, including the Hopi site of emergence into this world, according to traditional Hopi beliefs. The second project, called the Salt Trail Canyon Pumped Storage Project, would be similar in size and scope, located near a historic cultural route important to the affiliated tribes known as the Salt Trail, a few miles from the national park boundary.

The geological formations in this area have already seen their share of past developments. Some have caused long-lasting damage, such as uranium mining and loss of water from over-pumping of aquifers, which can stop free-flowing springs from reaching the canyon. These dams would intrude on Navajo Nation policy and legislation. They would violate designated protected areas including the Navajo Nation Little Colorado River Tribal Park, along with an agreement between the Navajo Nation and the Hopi Tribe protecting all of the Hopi Tribe’s cultural resources in this area. In the order issuing the two preliminary permits, FERC said concerns about the lack of tribal consultation, impacts to endangered species, and harm to cultural sites were premature and would be addressed in the next phase of the licensing process.

FERC is currently considering and will likely grant Pumped Hydro Storage LLC’s third preliminary permit application for the Big Canyon Pumped Storage Project, which the developers say would replace their earlier two proposals. The Big Canyon project includes four dams. Its lower reservoir would be built on the normally dry floor of the tributary Big Canyon, very near the proposed locations for the other two projects. The developers estimate they would need to pump about 14.3 billion gallons of groundwater from the underlying aquifer to fill the lower reservoir, plus another 3.2-4.8 billion gallons per year to make up for what is lost to evaporation.

ADAM HAYDOCK

ADAM HAYDOCK

This ancient, pristine aquifer would suffer greatly, as would the land, plants, animals, and people. The water that lies below and the river it feeds would be forever changed. Imagine this turquoise-blue water, free-flowing since our emergence into existence; now think of how long it would take to recharge this water which provides life for all. Are we willing to drain an aquifer so that the electricity generated could provide you with a luxurious life in your city?

We are not new to this idea of over-pumping for creating electricity that would benefit those in cities within the western United States. This has been done with the Mojave Generating Station and our N-Aquifer which does not supply adequate water to many communities, homes, and of course our springs which have now dried up. And with each development, the Navajo Nation and the Hopi Tribe are left without infrastructure to have this electricity delivered to homes.

While all three hydroelectric projects are on Navajo Nation land, Pumped Hydro Storage LLC has not sought the consent of the Navajo Nation, nor acknowledged any of the other tribes that maintain cultural connections to the Little Colorado River today. In 2008, The Navajo Nation designated the Little Colorado River Gorge as a biological preserve, which restricts all development that is not compatible with management goals for the preserve. But again, FERC says this is a premature concern at this point in the permitting process.

With preliminary permits in hand, the company now has exclusive rights for three years to conduct studies and determine the feasibility of the Salt Trail Canyon and Little Colorado River projects. Preliminary permits do not allow construction or grant right of entry to land, and developers must obtain necessary authorization and comply with laws and regulations to conduct field studies. Only if and when the company files a final license application will FERC require tribal consultation and compliance with the National Historic Preservation Act, Endangered Species Act, Clean Water Act, and other relevant laws.

This is not the first time outside developers have eyed the Little Colorado River as a source of personal profits. For nearly a decade, Scottsdale developers lobbied the Navajo Nation to approve the Grand Canyon Escalade, a mega-resort and tramway that would have carried up to 10,000 tourists a day to the sacred confluence. A group of local Navajo families called Save the Confluence opposed the project, spent years working to stop the Escalade proposal, and in 2017, the Navajo Nation Council slammed the door on the project by a vote of 16-2.

A few years later, a different threat looms, but the core issue remains: The Little Colorado River is not the right place for development for cultural reasons important to many tribal nations and those who have lived on the land for generations. We are all tied to this area by our shared stories, cultural history, and our prayers taught to us by our deities, which have been carried on through generations.

Again, local community members are raising their voices in opposition to development. The local landowners and ranchers of the area have individually opposed the dams. The local grazing district has passed resolutions opposing the projects. The Cameron Chapter of the Navajo Nation, where the projects would be built, unanimously passed a resolution denying Pumped Hydro Storage LLC its proposed feasibility study for the Little Colorado River and Salt Trail Canyon projects. The Navajo Nation has filed motions with FERC opposing all three projects. The Hopi Tribe, the Hualapai Tribe, and others have formally expressed their opposition to damming the Little Colorado River to FERC.

Citizens around the country are also voicing their support for area tribes. During FERC’s 60-day public comment period for the Big Canyon project that ended August 3, 2020, more than 60,000 Grand Canyon Trust supporters chimed in to protect the Little Colorado River.

Ultimately, the failed Escalade proposal and the three current dam projects have emphasized the need for permanent protection of the confluence area and the Little Colorado River. If it’s not a tram, or a dam, it will be a different development threat. The Little Colorado River is eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places as a traditional cultural property. And it is time for a review of how the local community members and tribal and federal agencies will address future threats. Exerting our voices as sovereign nations is long overdue, not individually but as collective voices from many tribes in unity having a say in how we manage our lands from a shared cultural standpoint and how to effectively co-manage our bordering lands with state, private, and federal landowners. Many of you have stood with us to stop these dams from damaging our pristine land, waters, and cultural sites. Ahéhee’ (Thank you).

Sarana Riggs is Chishi Diné from Big Mountain, Arizona. She manages the Grand Canyon Program and works to support Save the Confluence, a group of families that oppose the proposed Escalade development on the east rim of the Grand Canyon.

Also in this issue:

Tribal communities are rising to face COVID-19. Here's how you can help ›