BY SARANA RIGGS

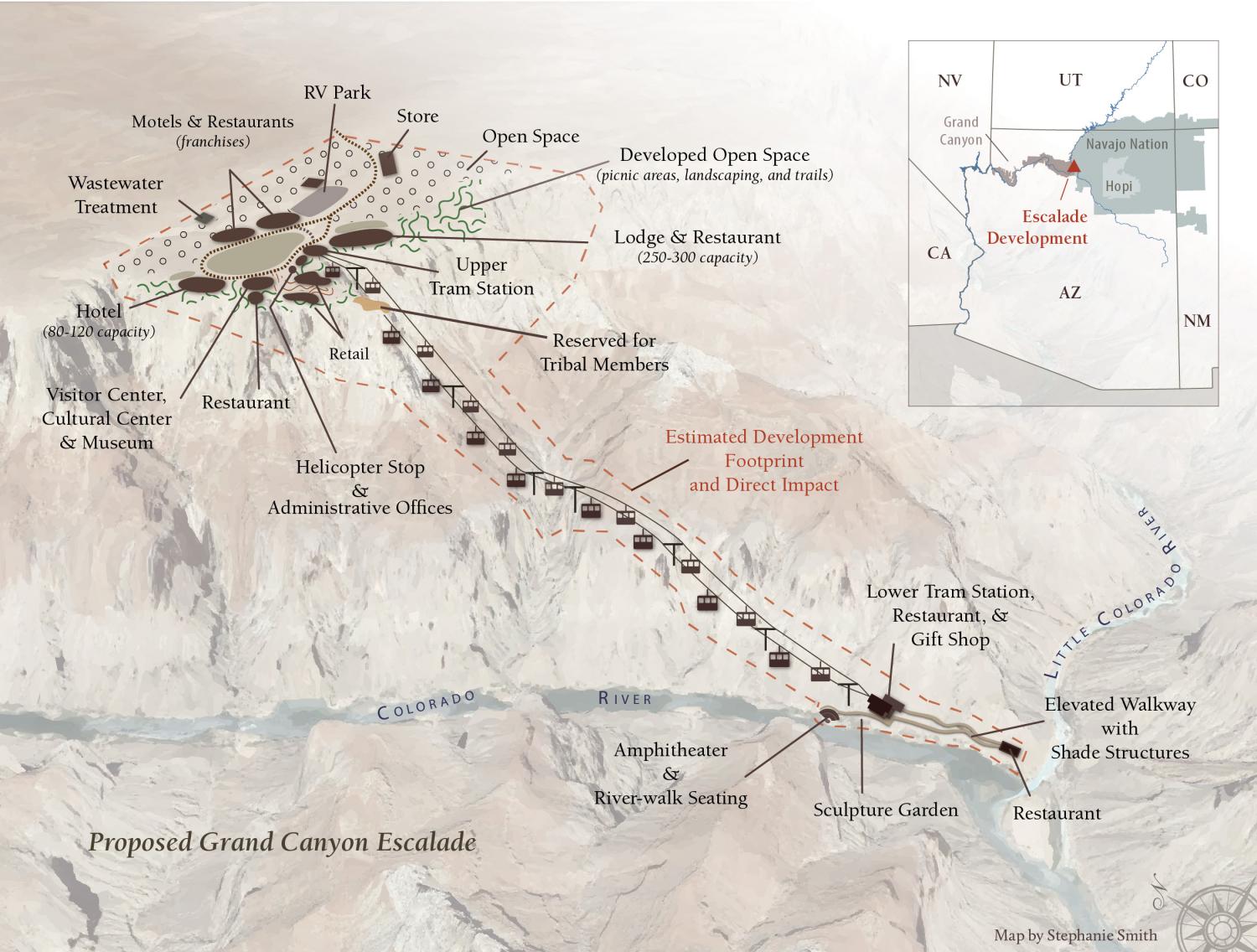

The Grand Canyon Escalade has been a heated debate since it first made its appearance in 2012. This 420-acre resort would include restaurants, retail stores, an RV park, a gas station, hotels, and, of course, the main attraction: a gondola to the bottom of the Grand Canyon.

The proposal has divided the Navajo Nation and the local community of Bodaway-Gap, Arizona, near the east rim of the Grand Canyon. I’ve been helping out Save the Confluence, a group of Navajo families who oppose the project, since 2012. The Grand Canyon Trust supports the families in their efforts to protect the canyon and their traditional ways of life. But as a Navajo woman and a mother of two boys, my connection to fighting this proposal is personal.

Escalade’s principal partner and biggest advocate is Scottsdale developer R. Lamar Whitmer. Speaking to National Geographic about the planned resort in 2016, Whitmer promised, “We’re going to employ an awful lot of people in an impoverished area and help them save their culture. What’s better than that?” In July 2017, he shared his high hopes with the Navajo Times, the tribe’s largest newspaper, saying, “Not just Navajos, but other people who will come here. They’ll be inspired, they’ll hear the stories, and they’ll be better people.”

These are hot topics at local chapter meetings all across the Navajo Nation, with employment being one of the top priorities. For some, the resort is a tangible option for individuals who want to support their families and stay closer to home where they can care for elders and be nearer to their culture. With the resort comes the promise of running water and electricity, luxuries for many in the Bodaway-Gap area, where people drive at least 30 miles one-way to get water. And supposedly, revenues from the project would save the Navajo Nation from the loss of royalties from Navajo Generating Station after the coal-fired power plant closes in 2019. But the nation would receive only a small percentage of the profits, not nearly enough once divided among 110 chapters and many government departments.

It has been nearly 150 years since the Navajo people were released from Bosque Redondo in New Mexico. Only a few generations ago, our Diné ancestors were forcibly removed from their homeland, known as Dinétah, and marched to Fort Sumner, New Mexico, which operated much like a concentration camp. In exchange for being allowed to return home, our ancestors signed a treaty that gave up their freedom and our rights as Diné and promised to live within an assigned boundary imposed by the United States government. In 1868, our ancestors returned home. As a people, we have been trying to heal from this trauma ever since.

Within the treaty came a mandate that all Navajo children be educated. Old forts were converted into schools, housing children from all corners of the Navajo Nation. This system of boarding schools took its cues from Richard Pratt’s view on indoctrination in the late 19th century: “kill the Indian, and save the man.” All Diné children were forced to speak English and punished if they were caught speaking their native tongue, including traditional prayers. The legacy of assimilation into mainstream society lives on in our youth today. The loss of cultural identity and language are of great concern for all Diné families.

After the Long Walk, the Navajo Nation Council was created in the 1920s to negotiate deals on natural resources that lay underneath Dinétah. Corporations moved in to stake claims on oil, uranium, coal, and natural gas, and with them came promises: jobs, water lines, electricity, and revenue for the Navajo Nation. The newly established government gave up lands, water, valuable resources, and our identity in exchange for these promises. Decades later, we are facing the heavy burdens of hundreds of abandoned uranium mines, drought, and mismanaged funds. And many of our people have yet to see water or electric lines to our homes. Those who were relocated so that companies could get to the mineral wealth beneath their homes now have no place to return.

But its promise comes at a very different price. Whitmer says that he will help save our culture. Which begs the question: How can you save culture by destroying culture? How is he saving our culture by building a resort at the western edge of Dinétah that would deface a sacred place?

Whitmer will never understand what this western boundary at the canyon means to us poor, underprivileged, third-world Indians. He does not understand the songs, prayers, and meaning behind our offerings. He does not speak or understand the languages of the many tribes he will be hurting. Our connection to this land and what our ancestors have gone through to preserve and protect it for our children is something we feel in our hearts and in our spirits. For us, the Grand Canyon is and forever remains a place of reverence and of spirituality. Blasting away at canyon walls to anchor a tramway here at the western edge of our nation and erecting buildings on the canyon’s rim will not symbolize and show its sacredness.

Exactly the opposite; it would show how money and man have once again attacked our culture in the name of prosperity, tourism, and the American dream. And try as he might to understand our religion by visiting and hiring a medicine man to perform a ceremony, Whitmer remains another ignorant outsider. He will never understand what it means to be Diné, Hopi, Havasupai, Hualapai, or any of the many other tribes who regard the Grand Canyon as home, a place of emergence, or a final resting place.

All tribes who have ancestral rights to the Grand Canyon are facing threats from uranium mining, contamination, exploitation, water shortages, overgrazing, and relocation to make room for developments, mining, and resource extraction. The truth in this whole matter is that commercialism and the shortsighted quest for prosperity are destroying our homelands. When our homelands are destroyed by resorts, pipelines, mines, and wells, and overrun with people, what will then happen to the people of the land? What will happen to our environment, our history, and all that we have worked to protect for future generations?

The balance of life is shifting, and we are not paying attention to the signs of climate change, movements of Mother Earth, and living beings disappearing from this world. The world has already tried to erase us from existence. It did not work, so the new strategy is to have our own people consent to erasure. We must stand up and fight for what is ours using every tool in our reach, from the laws already in place, to laws that must be created to further protect and preserve our ancestral lands, to, if need be, resistance. As long as there is breath in our bodies, we will honor and uphold what was taught to us by our elders.

Sarana Riggs is Chishi Diné from Big Mountain, Arizona. Since 2012, she has worked with Save the Confluence to oppose Escalade. In 2015, she joined the Grand Canyon Trust where she works on Native America volunteer and Grand Canyon projects.

Sarana Riggs is Chishi Diné from Big Mountain, Arizona. Since 2012, she has worked with Save the Confluence to oppose Escalade. In 2015, she joined the Grand Canyon Trust where she works on Native America volunteer and Grand Canyon projects.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The views expressed by Advocate contributors are solely their own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Grand Canyon Trust.

Also in this issue:

A uranium mine, a sacred mountain, and a tribe’s struggle to protect its drinking water. Read now ›